How s2n-quic uses Kani to inspire confidence

s2n-quic is a Rust implementation of the QUIC protocol, a transport protocol designed for fast and secure communication between hosts in a network. QUIC is relatively new, but it builds upon and learns from TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), the transport protocol that has been the standard for communication on the Internet for decades. TCP is the underlying protocol for HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2, but for the latest generation HTTP/3, QUIC is used instead. In that respect, QUIC can be thought of as a next-generation version of TCP with new features such as stream multiplexing and connection migration. However, the improvements over TCP go beyond just new features and functionality. Notably, QUIC is secure by default; the specification requires TLS be used within the QUIC handshake to establish encryption and authentication keys, and subsequently every QUIC packet is protected using these keys. With TCP, confidentiality and integrity were not part of the protocol design, and thus TLS was layered on top of TCP, as is done in HTTPS.

Requiring encryption by default is one of many improvements to security, functionality, and performance that the designers of the QUIC protocol learned from earlier protocols such as TCP. And similarly, when we implemented s2n-quic, we incorporated learnings from other protocol implementations. One of these learnings was the importance of using a verification tool like Kani to gain confidence in the properties we assert about critical code that is used for processing terabytes or more of data formatted, transmitted and encrypted as part of the QUIC protocol. In this blog post, I’ll show a few examples of how we use Kani to easily and automatically verify the correctness of our code, and ultimately inspire confidence in our team to continue improving and optimizing s2n-quic.

Optimizing weighted round trip time

Besides the importance of using Kani, another learning s2n-quic took to heart was that if a tool is not easy and minimally disruptive to use, it probably won’t get used much. For that reason, s2n-quic makes heavy use of the Bolero property-testing framework to add Kani’s verification functionality to our existing fuzz testing harnesses. This unification of multiple testing methods in a single framework has previously been covered in detail on this blog, but it’s worth revisiting to see how easy it makes incorporating Kani verification into s2n-quic. To illustrate this, I’ll dive into how we optimized an important component of s2n-quic, and in the next section we’ll see how we ensured the optimized code was correct by adding Kani to a Bolero fuzz test harness.

This particular code involves s2n-quic’s round trip time estimator. For context, in QUIC and other transport protocols, round trip time (or RTT) is the amount of time it takes a packet to be transmitted to a peer plus the time it takes for the peer’s acknowledgement of that packet to be received by the sender. RTT is an important measurement used throughout s2n-quic’s loss recovery and congestion control mechanisms. RTT is susceptible to natural variability, so s2n-quic calculates an exponentially weighted moving average called “smoothed RTT” each time the RTT is updated, which happens when a new packet acknowledgement has been received. The smoothed RTT is calculated by combining 7/8ths of the existing smoothed RTT measurement with 1/8th of the latest RTT measurement:

// smoothed_rtt and rtt are of type std::time::Duration

self.smoothed_rtt = 7 * self.smoothed_rtt / 8 + rtt / 8;

It turns out that this relatively straightforward implementation is less than optimal when compiled, resulting in three separate function calls in the assembly output:

mov edi, 7

**call qword ptr [rip + core::time::<impl core::ops::arith::Mul<core::time::Duration> for u32>::mul@GOTPCREL]**

mov r12, qword ptr [rip + <core::time::Duration as core::ops::arith::Div<u32>>::div@GOTPCREL]

mov rdi, rax

mov esi, edx

mov edx, 8

**call r12**

mov rbp, rax

mov ebx, edx

mov rdi, r15

mov esi, r14d

mov edx, 8

**call r12**

This smoothed RTT calculation is performed each time an acknowledgement is received from the peer, which could end up being thousands of times per second on a high bandwidth connection.

The contribution of these function calls to CPU utilization starts to add up in such a case.

Since s2n-quic is a lower level library that other applications are built upon, it needs to use as little CPU as possible to improve performance and reduce any impact to customer applications.

Fortunately, this implementation had a straightforward fix: converting from the Duration type used in the calculation to the primitive type u64, representing the number of nanoseconds in the duration.

let mut smoothed_rtt_nanos = smoothed_rtt.as_nanos() as u64;

smoothed_rtt_nanos /= 8;

smoothed_rtt_nanos *= 7;

let mut rtt_nanos = rtt.as_nanos() as u64;

rtt_nanos /= 8;

self.smoothed_rtt = Duration::from_nanos(smoothed_rtt_nanos + rtt_nanos);

This solution sacrifices a bit of unnecessary accuracy at the nanosecond level, but it eliminates the 3 function calls that were impacting CPU utilization:

mov rax, rcx

shr rax, 9

movabs rdx, 19342813113834067

mul rdx

mov rax, rdx

shr rax, 11

imul edx, eax, 1000000000

sub ecx, edx

mov edx, ecx

ret

Now that we have an optimized solution, we want to test that it has the same results (to the required level of precision) as the unoptimized code. Next, I’ll show how we do that with both fuzz testing and Kani verification in a single test harness.

From fuzz testing to Kani verification to continuous integration

The first way we can test this code is by writing a Bolero harness:

#[test]

fn weighted_average_test() {

bolero::check!()

.with_type::<(u32, u32)>()

.for_each(|(smoothed_rtt, rtt)| {

let smoothed_rtt_nanos = Duration::from_nanos(*smoothed_rtt as _);

let rtt_nanos = Duration::from_nanos(*rtt as _);

let weight = 8;

// assert that the unoptimized version matches the optimized to the millisecond

let expected = ((weight - 1) as u32 * smoothed_rtt) / weight + rtt / weight;

let actual = super::weighted_average(smoothed_rtt, rtt, weight as _);

assert_eq!(expected.as_millis(), actual.as_millis());

})

}

This harness will fuzz test the smoothed RTT calculation code (extracted out into the weighted_average function) by generating u32 values according to the multiple fuzzing engines that Bolero supports.

These values are then used in both the original, unoptimized version of the code, as well as the optimized weighted_average function, to assert that both versions match with millisecond precision.

This technique is called “differential testing” and is a powerful method for identifying logical differences between multiple versions of code.

The Amazon Science blog recently highlighted the value of using this technique with the AWS Cedar authorization engine.

Now we have a fuzz test to ensure the assertion that the optimized and unoptimized code result in the same millisecond result holds over millions of different combinations of smoothed_rtt and rtt values.

But what if we want to prove that this assertion is true for all combinations of smoothed_rtt and rtt?

That’s where Kani comes in.

Upgrading this fuzz test to a fuzz + verification test is as easy as adding a few config attributes to the existing test harness:

#[test]

#[cfg_attr(kani, kani::proof, kani::solver(kissat))]

fn weighted_average_test() {

The kani::proof attribute lets Bolero know that this test harness can be run as a Kani proof.

kani::solver(kissat) is an optional attribute we can add to specify the solver used in Kani’s verification engine.

We like using the Kissat SAT Solver in s2n-quic as it has good performance for the type of code we are typically verifying.

No one solver is the best at everything, though, so some testing and comparison may be necessary for your use case.

We can run this particular test on the command line and see that the verification is successful:

$ cargo kani --harness recovery::rtt_estimator::test::weighted_average_test --tests

...

SUMMARY:

** 0 of 344 failed (1 unreachable)

VERIFICATION:- SUCCESSFUL

Verification Time: 44.769085s

Running the Kani verification ad-hoc like this is helpful when writing test harnesses or trying different configurations. But another thing we’ve learned when implementing s2n-quic is that if a test isn’t run automatically and on a regular basis, we can’t consider the code to be tested. And that is why we run Kani proofs as part of the continuous integration (CI) suite of tests that run every time an s2n-quic code change is proposed in a pull request and whenever code is merged into main. This is accomplished using the Kani Rust Verifier Action, a GitHub action that lets us easily execute Kani verification as part of a CI workflow. The s2n-quic CI runs many different types of tests, including unit tests, integration tests, snapshot tests, performance benchmarking, interoperability testing, and the aforementioned fuzz testing. All of these tests use different techniques, but collectively they ensure s2n-quic functions as our customers expect even as we continue to add new features and optimize for performance. Adding Kani to our suite of automated testing provides us with yet another approach to validate the correctness of s2n-quic and increase our confidence in the software, all with a minimum amount of incremental effort. If you want to learn how to setup the Kani action on your own GitHub repository, see Easily verify your Rust in CI with Kani and Github Actions. Next we’ll take a look at a real world instance where Kani was able to catch a bug well before it made it to production.

Catching a bug in packet number decoding

Another learning that QUIC took from TCP was the importance of knowing the ordering in which packets are transmitted. In TCP, a receiver must infer the order a packet was transmitted, making it harder to determine when a packet has been lost, versus just re-ordered or delayed. This introduces ambiguity into the RTT calculation I described earlier, as it is not always clear if the packet took longer to be acknowledged because the network slowed down or if it had been lost and subsequently retransmitted. To address these issues, QUIC assigns a monotonically increasing packet number to every QUIC packet, included retransmissions, that explicitly indicates the order in which a packet was transmitted.

The packet number is a value ranging from 0 to 2^62-1. While such a large range is necessary for supporting long running connections that may send many packets, it also would consume 8 bytes of every packet. 8 bytes might not sound like much, but with s2n-quic being used to send billions of packets back and forth, it adds up and ultimately increases the overhead of using the QUIC protocol. Therefore, the packet number is encoded in 1 to 4 bytes, following a process that truncates the most significant bits of the packet number based on some assumptions about how wide a range of packet numbers could be in flight at a given time.

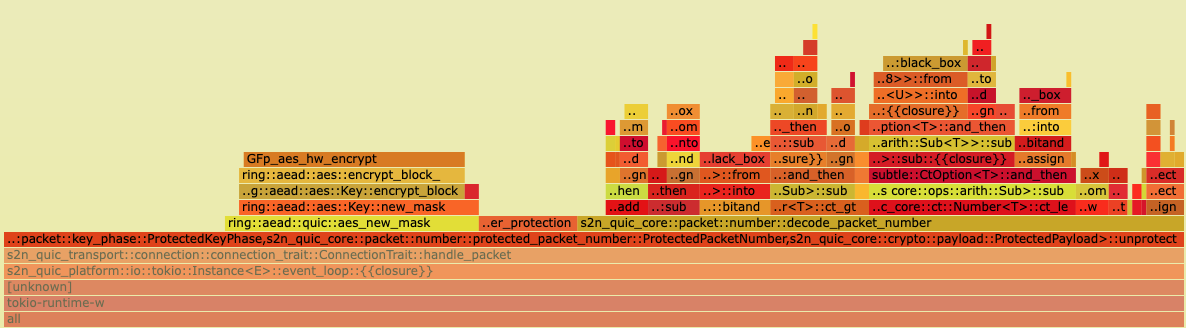

We noticed that s2n-quic’s function for decoding the packet number, decode_packet_number, was showing up in the CPU flame graphs that the s2n-quic CI generates based on a range of common traffic patterns.

If you haven’t seen a flame graph before, the important thing to take away is the wider the box containing each function is, the more relative CPU time that particular function is using.

From the flame graph below we can see the s2n_quic_core::packet::number::decode_packet_number function is consuming the bulk of the CPU time needed to unprotect the packet, representing about 2% of the total CPU used for processing a packet.

The QUIC RFC requires this packet decoding process be free of timing side channels, which our initial implementation ensured by using volatile read operations at the expense of additional CPU utilization.

As was the case with the RTT estimator, there is room for optimization here.

We found that by supplying some additional compiler instructions we could refactor decode_packet_number in a way that would fulfill the constant-time requirement from the RFC while avoiding the expensive volatile read operations.

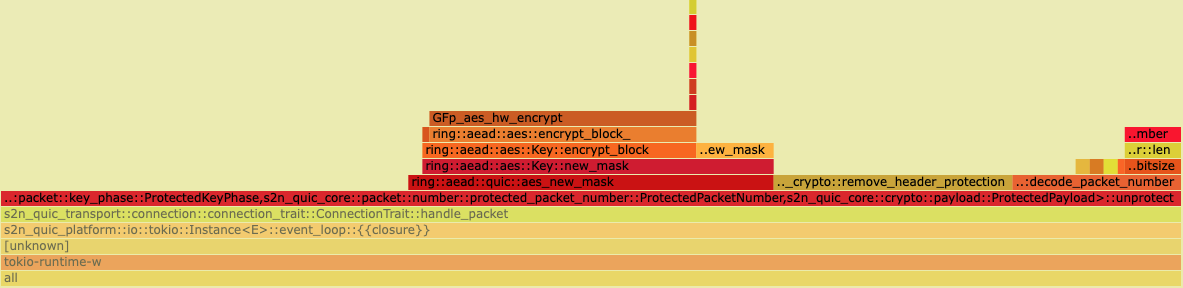

With these optimizations, the CPU usage of decode_packet_number became so small it barely showed up in the flame graph at all:

All good, right? Not so fast…

$ cargo kani --harness packet::number::tests::rfc_differential_test --tests

...

SUMMARY:

** 1 of 760 failed (1 unreachable)

Failed Checks: assertion failed: candidate_pn <= VarInt::MAX.as_u64()

File: "/s2n-quic/quic/s2n-quic-core/src/packet/number/mod.rs", line 235, in packet::number::decode_packet_number

VERIFICATION:- FAILED

Verification Time: 2.8690908s

The Kani proof on the rfc_differential_test has failed!

rfc_differential_test is another example of a differential test using Bolero, like we saw for testing the smoothed RTT calculation:

#[test]

#[cfg_attr(kani, kani::proof, kani::solver(kissat))]

fn rfc_differential_test() {

bolero::check!()

.with_type()

.cloned()

.for_each(|(largest_pn, truncated_pn)| {

let largest_pn = new(largest_pn);

let space = largest_pn.space();

let truncated_pn = TruncatedPacketNumber {

space,

value: truncated_pn,

};

let rfc_value = rfc_decoder(

largest_pn.as_u64(),

truncated_pn.into_u64(),

truncated_pn.bitsize(),

)

.min(VarInt::MAX.as_u64());

let actual_value = decode_packet_number(largest_pn, truncated_pn).as_u64();

assert_eq!(actual_value, rfc_value, "diff: {:?}",

actual_value.checked_sub(rfc_value)

.or_else(|| rfc_value.checked_sub(actual_value))

);

});

}

This test runs both the decode_packet_number implementation from above as well as an alternate implementation (rfc_decoder) that exactly follows the pseudocode the QUIC specification provides for decoding packet numbers.

If the result from the two implementations differ, the test will fail.

In this case, the test failed even before decode_packet_number produced a result, as the following assertion no longer held true:

debug_assert!(candidate_pn <= VarInt::MAX.as_u64());

It turns out that a simple min operation that had been applied to candidate_pn in the unoptimized code had been removed during the optimization process.

Kani saved us from merging this potential bug! One quick fix later, and the verification now succeeds:

$ cargo kani --harness packet::number::tests::rfc_differential_test --tests

...

SUMMARY:

** 0 of 760 failed (1 unreachable)

VERIFICATION:- SUCCESSFUL

Verification Time: 2.7241826s

For this example, using Bolero to run rfc_differential_test as a fuzz test also reveals the bug after running for less than a minute.

In the next example, we’ll see that this is not always the case.

Fitting Stream frames into a QUIC packet

Continuing on the theme of using CPU and bytes as efficiently as possible, the QUIC protocol uses variable-length encoding for most integers written into QUIC packets and frames.

This allows for a wide range of integers to be represented while requiring less bytes for smaller values.

This is accomplished by repurposing the first 2 bits of the first byte of an integer to indicate the total length of the integer, which may be either 1, 2, 4 or 8 bytes.

For example, if the first 2 bits of the first byte are 00, this means the integer is 1 byte long and may represent a number in the range 0 to 63 (2^6 - 1) in the remaining 6 bits of the first byte.

If the first 2 bits of the first byte are 01, the integer is 2 bytes long and thus can represent integers from 0 to 2^14 - 1, with 6 usable bits left in the first byte and 8 bits in the second byte, for a total of 14 bits.

An interesting property arises when this variable-length encoding is used to encode the length of data contained within a frame, as is done with the Stream frame that carries the majority of data transmitted over a QUIC connection.

s2n-quic tries to fit as much data as possible in each Stream frame, based on how much remaining capacity is available in the QUIC packet the frame is being written to.

Since the size of the variable-length integer used to represent the Stream data length depends on the length of the value it is encoding, trying to fit one more byte of data into a packet may end up also increasing the size of the variable-length integer, resulting in the Stream frame not fitting anymore! For example, say that a packet has 65 bytes of available capacity.

If we try to fit 63 bytes of data in this packet, this will consume 64 bytes from the packet, as the length of 63 can be encoded in 1 byte, as we saw above.

We have 65 bytes to work with though, so why not try to fit one more byte? A length of 64 requires 2 bytes to encode, so now the total amount we’ve consumed is 2 bytes + 64 bytes = 66 bytes, more than the available capacity.

The logic s2n-quic uses to determine how much data to try to fit in a Stream frame is contained in the function try_fit.

With complicated logic like this, we have a Bolero test harness to validate the correctness of the logic:

#[test]

#[cfg_attr(kani, kani::proof, kani::solver(kissat))]

fn try_fit_test() {

bolero::check!()

.with_type()

.cloned()

.for_each(|(stream_id, offset, length, capacity)| {

model(stream_id, offset, length, capacity);

});

}

The model function called in this test constructs a Stream frame with the given inputs, tries to fit it into a packet with the given capacity, and makes several assertions about the result.

Let’s first run this test harness using the libfuzzer fuzzing engine:

$ cargo bolero test frame::stream::tests::try_fit_test --engine libfuzzer

#65536 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 659 exec/s: 21845 rss: 63Mb

#131072 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 1308 exec/s: 21845 rss: 69Mb

#262144 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 2609 exec/s: 21845 rss: 82Mb

#524288 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 4096 exec/s: 22795 rss: 107Mb

#1048576 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 4096 exec/s: 22310 rss: 157Mb

#2097152 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 4096 exec/s: 22550 rss: 258Mb

#4194304 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 4096 exec/s: 22429 rss: 460Mb

#8388608 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 4096 exec/s: 22429 rss: 522Mb

#16777216 pulse cov: 119 ft: 175 corp: 16/330b lim: 4096 exec/s: 22429 rss: 525Mb

The last line of output indicates that libfuzzer has tried more than 16 million different inputs at a rate of 4096 executions per second, and so far no assertions have failed. This took over 10 minutes to run, and letting it run even longer still failed to find any failures. Let’s see what Kani thinks:

$ cargo kani --harness frame::stream::tests::try_fit_test --tests

SUMMARY:

** 1 of 561 failed (1 unreachable)

Failed Checks: assertion failed: frame.encoding_size() == capacity

File: "/s2n-quic/quic/s2n-quic-core/src/frame/stream.rs", line 322, in frame::stream::tests::model

VERIFICATION:- FAILED

Verification Time: 20.149725s

Kani found a failure in only 20 seconds!

It turns out in this case that the bug was the model function itself being overly strict, but it could have just as easily been a bug in the try_fit implementation.

This example highlights yet another learning for s2n-quic: the value of defense in depth.

We’re strong believers in the Swiss cheese model, in which each layer of cheese may contain many holes (such as the fuzz test above missing out on the failure), but combining the layers together greatly reduces the chance that a hole reaches all the way through.

A single testing technique may not catch every issue, but layering fuzz testing, Kani verification, and all the other testing methodologies s2n-quic employs vastly improves the likelihood that at least one test will catch a bug before it reaches production.

Conclusion

s2n-quic has a very high bar for software quality, as any bug in a transport protocol implementation can have drastic consequences for the customers that rely on the library as the foundation for the applications and services they are building. I’ve shown above how Kani helps us meet that bar with a vanishingly small amount of effort by easily integrating with our existing Bolero fuzz test harnesses and automatically running as part of our continuous integration test suite. And even better than catching bugs in the wild, Kani has helped s2n-quic catch bugs before they make it any further than a pull request, even when a fuzz test was unable to. As of now, s2n-quic has over thirty Bolero harnesses with Kani enabled, spanning many critical parts of the codebase. As we continue to add more and more proofs and increase code coverage, Kani gives us the confidence to continue optimizing and improving s2n-quic while ensuring the correctness our customers require.

Author bio

Wesley Rosenblum is a Senior Software Development Engineer at AWS. Over his 16 year career at Amazon he has designed and implemented software ranging from automated inventory management services to open source encryption libraries. He has spent the past 3 years working on s2n-quic, with a particular focus on the loss recovery and congestion control algorithms that are critical for performance and reliable data delivery.