Internship Projects 2022: Concrete Playback

Today we’re starting a series of posts about the internship projects carried out in our team during 2022. The Kani team is proud to be part of the AWS Automated Reasoning teams, which every year host a number of interns to work on automated-reasoning projects for tools like Kani. More details on AWS Automated Reasoning areas of work and available locations can be found here. If you’re a Masters or PhD student interested in Automated Reasoning, please consider applying to the following openings:

This internship project was executed by Sanjit Bhat. Sanjit joined the Kani team as an SDE Intern while finishing his undergraduate studies at UT Austin and is now a PhD student at MIT. We are very grateful to Sanjit for his hard work on this project, and wish him the best in his PhD studies!

Proof Debugging

We commonly use the term Proof Debugging to refer to the process of debugging failing proofs that we expected to succeed. The process isn’t very different to debugging unit tests: There’s one or more errors due to assumptions made about the function under test, and how the inputs and/or outputs relate to that function. The goal then is to find what assumption was mistakenly made and correct it accordingly.

Let’s talk about how tooling can make this process easier for users.

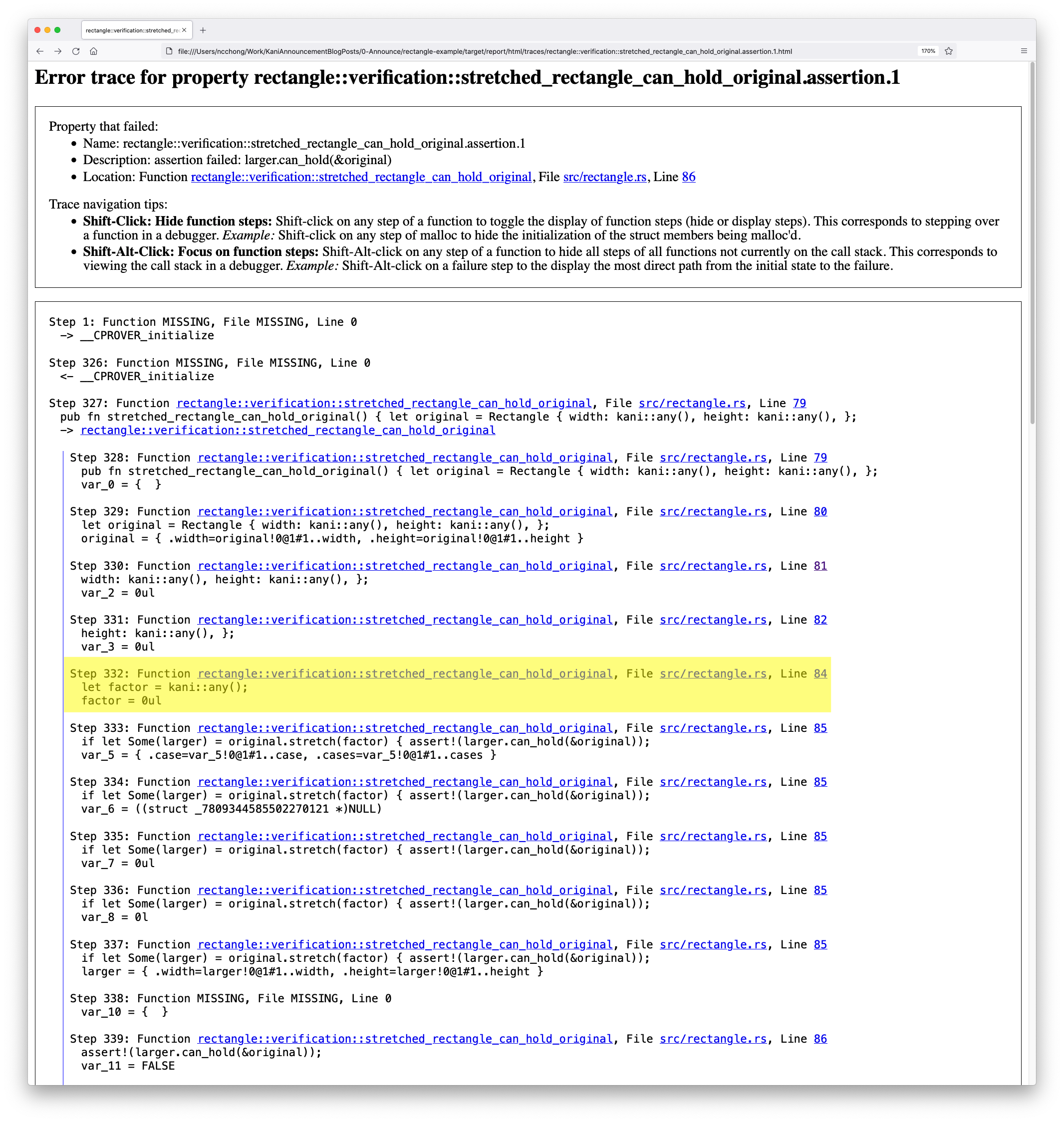

CBMC Viewer

As you may know, Kani uses CBMC to perform the main analysis required for verification. When one or more checks have failed, that’s a verification failure. In these cases, CBMC can return a text-based trace which includes the sequence of steps leading to the failed check. We often call this trace a counter-example.

Until now, the main tool for proof debugging in Kani was

cbmc-viewer. cbmc-viewer is

an open-source tool that scans different formats of CBMC traces and produces a

browsable HTML report based on that output. Thanks to this tool, the trace can

be seen in a regular HTML browser:

However, CBMC traces for real-world examples may include a huge number of steps. This means proof debugging is difficult, as the user has to identify what steps are relevant to the proof failure and understand at a high-level what the trace is computing (i.e., the user has to interpret the whole trace).

This made us think:

Wouldn’t it be great to get those values automatically? Or even better, could we generate programs that exercise the path in that particular trace?

We realized this would ease proof debugging for many users, so we set ourselves to design and develop such a feature for Kani.

Concrete Playback

An example

Remember the rectangle example we used in our announcement? We will use the same example to illustrate how concrete playback works. Feel free to skip up to the next section if you’re familiar with it.

As a quick reminder, we started with the Rectangle implementation from the Rust book:

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct Rectangle {

width: u64,

height: u64,

}

impl Rectangle {

fn can_hold(&self, other: &Rectangle) -> bool {

self.width > other.width && self.height > other.height

}

fn stretch(&self, factor: u64) -> Option<Self> {

let w = self.width.checked_mul(factor)?;

let h = self.height.checked_mul(factor)?;

Some(Rectangle { width: w, height: h })

}

}

And this is the harness we wrote:

#[kani::proof]

pub fn stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original() {

let original = Rectangle { width: kani::any(), height: kani::any() };

let factor = kani::any();

if let Some(larger) = original.stretch(factor) {

assert!(larger.can_hold(&original));

}

}

Note that verification will fail when the harness above is run with Kani:

cargo kani --harness stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original

# --snip--

VERIFICATION:- FAILED

If we run the command with --visualize, cbmc-viewer would generate the

report we showed in the CBMC Viewer section. The highlighted

step there, which assigns factor = 0ul, is the concrete value we’d look for.

Now we’ll see how to run concrete playback on this example.

Concrete playback in action

In order to run concrete playback, we have to invoke Kani with the --concrete-playback=<mode> flag.

Here, mode can be either print or inplace.

Also, because concrete playback is an unstable feature, we’ll need to pass --enable-unstable in addition to the other flags.

Let’s try the print mode first!

cargo kani --harness stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original --enable-unstable --concrete-playback=print

Aside from the usual results, we now see additional output:

INFO: Parsing concrete values from property `rectangle::stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original.assertion.1` with description `assertion failed: larger.can_hold(&original)`.

Concrete playback unit test for `stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original`:

```

#[test]

fn kani_concrete_playback_stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_11077055701284606517() {

let concrete_vals: Vec<Vec<u8>> = vec![

// 0ul

vec![0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

// 301283365829122ul

vec![2, 58, 255, 255, 3, 18, 1, 0],

// 36573ul

vec![221, 142, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

];

kani::concrete_playback_run(concrete_vals, stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original);

}

```

INFO: To automatically add the concrete playback unit test `kani_concrete_playback_stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_11077055701284606517` to the src code, run Kani with `--concrete-playback=InPlace`.

With the print mode, concrete playback generates a Rust unit test that:

- Initializes a vector of byte vectors with concrete values.

- Runs the harness we tested with those concrete values.

The way the vector concrete_vals is initialized may be confusing at first.

But if you look closely, you’ll realize that each vector contained in the main

vector is a sequence of eight bytes (or u8 values), which is just another way

to represent a u64 value. In summary, Kani requires each variable assigned

kani::any() in our harness (factor, width, and height) to be initialized

byte by byte, and that’s why we need three 8-byte vectors.

Because bytes are not easy to read for humans, we add a comment above each byte

vector with the value it represents.

Now let’s run Kani with the inplace mode:

cargo kani --harness stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original --enable-unstable --concrete-playback=inplace

# --snip--

INFO: Parsing concrete values from property `rectangle::stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original.assertion.1` with description `assertion failed: larger.can_hold(&original)`.

INFO: Now modifying the source code to include the concrete playback unit test `kani_concrete_playback_stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_11077055701284606517`.

The test unit that was printed out is added to the source code automatically! Now we can run the test that Kani inserted into the source code, which can be done1 with the default command for running Rust unit tests:

cargo +nightly test

running 1 test

test rectangle::tests::kani_concrete_playback_stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_11077055701284606517 ... FAILED

failures:

---- rectangle::tests::kani_concrete_playback_stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_11077055701284606517 stdout ----

thread 'rectangle::tests::kani_concrete_playback_stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_11077055701284606517' panicked at 'assertion failed: larger.can_hold(&original)', src/rectangle.rs:36:9

note: run with `RUST_BACKTRACE=1` environment variable to display a backtrace

failures:

rectangle::tests::kani_concrete_playback_stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_11077055701284606517

test result: FAILED. 0 passed; 1 failed; 0 ignored; 0 measured; 0 filtered out; finished in 0.00s

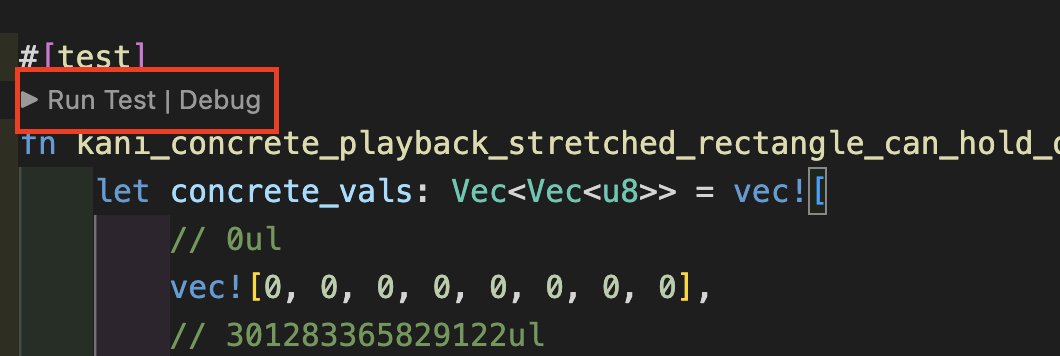

In fact, if you’ve configured your IDE with

rust-analyzer, you may even run or debug

the test using the options that appear around the #[test] annotation.

In VSCode, for example, they can be found

below.

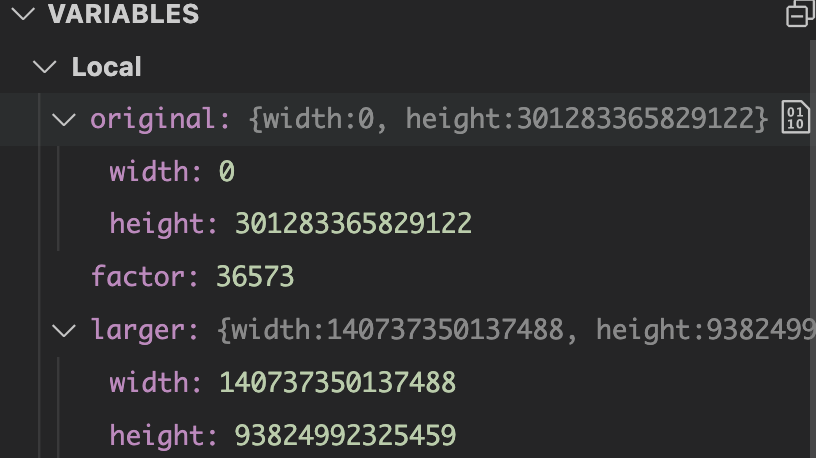

In particular, the Debug mode may be really useful to debug complex traces.

Setting up a breakpoint before the line that triggers the failure and running

Debug will allow you to inspect the values of all variables at that point.

In most cases, this information should be enough to properly debug the proof you were working on!

There are some neat details about the inplace mode that have been implemented

after watching our users trying out the feature.

For example, the name of the test contains a hash value that depends on the

concrete values, to avoid having repeated unit tests in the code.

Another improvement is that Kani will format the code with rustfmt after

adding the test to the source code, so we keep it formatted at all times.

How it all works

We won’t go in detail about how the concrete playback feature works, but here’s an overview of the main tasks for this project:

- Implement parsing of CBMC traces to retrieve concrete values from

kani::any()variable initializations. - Provide an alternative implementation of

kani::any()which initializes variables using the concrete values collected using the implementation in (1). - Add the logic to print, format, and (optionally) write a Rust unit test with the extracted concrete values.

- Add a flag for the concrete playback feature, and extend Kani’s workflow to perform the previous tasks automatically when using that flag.

That should give you an idea of how the project was structured.

Please go ahead and try the concrete playback feature yourself!

Note that it comes with a few limitations explained here. We have other improvements in mind for it, but let us know if you have any ideas. We especially encourage you to file a bug report if you come across any error when using it as well.

Overall, we had a lot of fun working with Sanjit on this project, and we’re confident it’ll be very useful for Kani users in the future!

Footnotes

-

This assumes that you’ve completed these setup instructions, which require adding the Kani library to

[dev-dependencies], and that you have access to the nightly version of the Rust toolchain. ↩