Announcing the Kani Rust Verifier Project

Today we’re excited to tell you about the first release of the Kani Rust Verifier (or Kani, for short), an open source automated reasoning tool for proving properties about your Rust code. Like other automated reasoning tools, Kani provides a way to definitively check, using mathematical techniques, whether a property of your code is true under all circumstances. In this way, Kani helps you write better software with fewer bugs.

As developers, we love the Rust programming language because of its focus on performance, reliability and productivity. Out of the box, Rust is fast (it does not require a runtime or garbage collector) and safe in the sense that its strong type system and ownership model can statically guarantee memory and thread-safety by default. This is an excellent foundation, but Rust still needs testing and automated reasoning tools to address properties beyond type safety, such as when a developer would like assurances about properties such as absence of runtime errors or functional correctness. Alternatively, a developer may need low-level control (e.g., for performance or resource efficiency) that is too subtle for the compiler to understand, so they must use unsafe Rust, which is not fully checked by the compiler. In cases like these, testing and automated reasoning tools can provide complementary and extended assurances to the built-in capabilities of Rust.

We see a future where there is a smooth path for Rust developers to adopt as much testing and automated reasoning as they feel is appropriate for their project’s needs. A journey with lots of stops along the way: from the familiar built-in testing capabilities of the language, to automated testing with MIRI and sanitizers, to fuzzing and property-based testing, and then lightweight automated reasoning tools, such as MIRAI and now Kani, that prove simple requirements, and finally automated reasoning tools such as Creusot and Prusti that prove more-involved requirements. We imagine a wide spectrum of tools to help developers ensure that their code is secure and correct. This is not a new idea. For example, we were inspired by Alastair Reid’s blog posts about the complementary nature of testing and automated reasoning (also known as formal verification) and the call to try to have both. Here’s a sketch of a subway map of exciting stops:

Prusti

Sanitizers | ,--o----+ ,--o----- ...

,---o-----o---+ \ / MIRI | /

/ A T | X o MIRAI /----o----- ...

/ +-o----` `\ | / Creusot

----o-` Fuzzing \ +---o----o----

Testing RVT Kani

We see Kani as contributing to this future. We’re focusing on the initial change that occurs when moving from testing to automated reasoning. In the journey above, there’s a conceptual change from dynamic testing, which works by executing the code, to automated reasoning, which works by analyzing the code without having to execute it. This difference might make you think that we need a whole new way of approaching the problem, or that you might need expertise beyond what you’re already used to for testing. We think there’s an opportunity to make this change as small and straightforward as possible by building on top of your existing knowledge and familiarity with testing. Getting started with automated reasoning should be as straightforward as taking existing unit tests and reusing them so that automated reasoning tools, like Kani, can analyze them.

If you have ideas in this space then come find us and other friendly groups interested in bringing more automated reasoning to Rust in the Rust Formal Methods Interest Group (RFMIG) which has schedule of meetings open to all. We gave a talk at RFMIG on March 28th 2022.

A simple example

Here’s an example to show some of the journey we’re envisioning. It’s hard to pick an example that’s straightforward, shows you the key ideas and is realistic at the same time. In this first post, we’re focused more on the first two (being straightforward and showing you the key ideas). In follow up posts we will apply Kani to real-world examples, including the Rust Standard Library, Tokio and the Firecracker virtual machine monitor.

We start with an implementation of a Rectangle from the Rust Book.

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct Rectangle {

width: u64,

height: u64,

}

impl Rectangle {

fn can_hold(&self, other: &Rectangle) -> bool {

self.width > other.width && self.height > other.height

}

}

Let’s add a transform that stretches a rectangle by a given factor where we carefully check for integer overflow using checked_mul, which returns None if overflow occurs.

[In Rust, integer overflow is not undefined behavior (as in C for signed integer overflow).

If we had instead chosen to use the “bare” operation (e.g., self.width * factor) then we would have to handle possible runtime panics or wraparound when compiling our example in debug or release mode, respectively.]

impl Rectangle {

fn stretch(&self, factor: u64) -> Option<Self> {

let w = self.width.checked_mul(factor)?;

let h = self.height.checked_mul(factor)?;

Some(Rectangle {

width: w,

height: h,

})

}

}

First stop: unit testing

How can we test our code so that we can sure that we’ve implemented what we expect? How about saying when a stretched rectangle can hold its original size? Let’s begin with a familiar friend: unit tests.

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

use super::*;

#[test]

fn stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original() {

let original = Rectangle {

width: 8,

height: 7,

};

let factor = 2;

let larger = original.stretch(factor);

assert!(larger.unwrap().can_hold(&original));

}

}

Easy!

With a quick cargo test we can run the test above and see it pass.

$ cargo test

# --snip--

test rectangle::tests::stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original ... ok

Moving onto property-based testing

What if we wanted to go further? The next stop of our journey is property-based testing, which is a kind of fuzzing. A key idea of property-based testing is that we want to assert properties that should be true for any test case, not just the concrete ones we have in unit tests.

One framework for property-based testing in Rust is proptest.

Using this framework, we can write a test harness that takes 3 parameters: a width, height and factor.

The harness asserts that if we stretch a rectangle initially of size (width, height) by factor and if stretch returns Some(...) then the resulting rectangle must be large enough to hold the original.

In effect, the harness is a template that proptest can generate many concrete tests for by choosing random values for width, height and factor.

#[cfg(test)]

mod proptests {

use super::*;

use proptest::prelude::*;

use proptest::num::u64;

proptest! {

#[test]

fn stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original(width in u64::ANY,

height in u64::ANY,

factor in u64::ANY) {

let original = Rectangle {

width: width,

height: height,

};

if let Some(larger) = original.stretch(factor) {

assert!(larger.can_hold(&original));

}

}

}

}

Now each cargo test will generate thousands of random rectangles to test our code.

For not much extra effort we’ve increased our assurance in the correctness of our code, which is great!

We think property-based testing is a powerful idea.

For example, proptest was one technique used by Amazon S3 to validate a key-value storage node.

$ cargo test

# --snip--

test rectangle::proptests::stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original ... ok

What if we wanted to go further?

Each run of proptest runs thousands of test cases that pass—but is that enough to know our assertion can never fail?

One way to be sure is to exhaustively test all possible values for the parameters.

Proptest is super but can’t help us reach that bar.

There are three u64 parameters (width, height, and factor).

Since each parameter can take one of 2^64 values there are 2^64 * 2^64 * 2^64 = 2^192 possible test cases.

That’s a large number: even testing at a rate of 10^9 cases a second (1 test case every nanosecond) would take longer than the age of the universe (~14bn years).

Enter Kani!

Wouldn’t it be cool to exhaustively test all possible inputs in a reasonable amount of time? With automated reasoning techniques, we can effectively do that! Our next stop on our journey will use Kani. We will write a harness like so:

#[cfg(kani)]

mod verification {

use super::*;

#[kani::proof]

pub fn stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original() {

let original = Rectangle {

width: kani::any(),

height: kani::any(),

};

let factor = kani::any();

if let Some(larger) = original.stretch(factor) {

assert!(larger.can_hold(&original));

}

}

}

Notice how similar the setup looks to the proptest harness.

One change you’ll notice is we’re using a automated reasoning-only feature: any().

This is a neat feature that informally says “consider any u64 value”.

This is not the same as a randomly chosen concrete value as in proptest but rather a symbolic value that represents any possible value of the appropriate type.

One way of reading this harness is that we’re asking Kani a question: “can you find a choice of values for width, height and factor where each can be any u64 value such that we can fail the assertion?”

Unlike unit testing or property-based testing (or testing in general), Kani is not based on dynamically executing the code. Rather Kani works by statically analyzing the code. Because of this, Kani is able to answer the question above in less than a second.

$ cargo kani --harness stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original

# --snip--

[rectangle::verification::stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original.assertion.1] line 86 assertion failed: larger.can_hold(&original): FAILURE

VERIFICATION FAILED

This result might seem unexpected! Kani has possibly uncovered some problems with the assertions in our harness. Can you see them too?

Hint

What about corner cases, such as if the rectangle starts with `width == 0`?

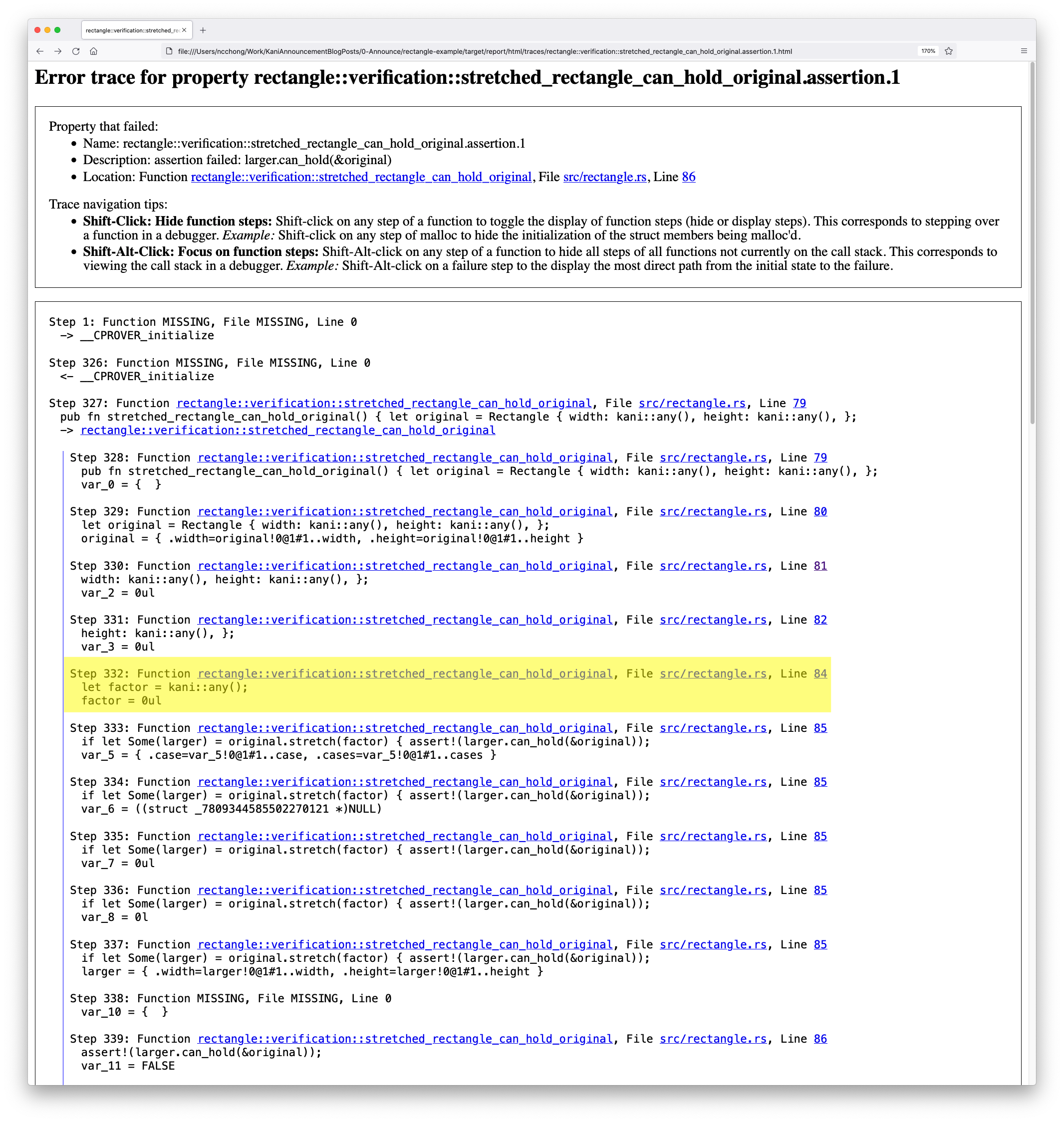

Currently the debug output from the tool is given as a trace that steps through an execution of the program.

In the future, we want to be able to plug into your favorite IDE to debug/step-through the trace interactively and even envision auto-generating failing test cases.

For now, here’s a sample of what the output from Kani looks like (notice the --visualize option):

$ cargo kani --harness stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original --visualize

# --snip--

# generates the following html report...

The trace starts with the entry to the harness and ends with the failing assertion.

In this particular trace we see that factor is 0 (at Step 332, which we’ve highlighted).

In fact, this is a problem if any of the parameters are zero.

In this case, stretch will return Some(...) but the stretched rectangle will not be large enough to hold the original since at least one of its sides will be zero length.

Additionally, there is a problem if factor is 1 because in this case stretch will return Some(...) but the stretched rectangle will be the same size as the original.

We missed these cases in our unit and property-based tests.

Automated reasoning tools like Kani force us to think through corner cases like these.

There are a few ways we might address this.

One way would be to add these requirements to stretch to forbid calling this method on rectangles in these cases.

For this example, so that we can show another feature of Kani, let’s explicitly call out these requirements in our harness.

This might seem pedantic, but having these requirements be called out explicitly (rather than in comments or relying on convention) is valuable as a kind of executable documentation.

#[cfg(kani)]

mod verification {

#[kani::proof]

pub fn stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_fixed() {

let original = Rectangle {

width: kani::any(),

height: kani::any(),

};

let factor = kani::any(); //< (*)

kani::assume(0 != original.width); //< explicit requirements

kani::assume(0 != original.height); //<

kani::assume(1 < factor); //<

if let Some(larger) = original.stretch(factor as u64) {

assert!(larger.can_hold(&original));

}

}

}

In this harness, we use another automated reasoning feature: assume, which we use to tell the analysis to constrain the possible values of width, height and factor.

This harness covers 2^192 test cases.

With these changes, the harness can be read as asking Kani: “can you find a choice of values for width, height and factor where width and height are any non-zero u64 values and factor is any u64 value greater than one such that we can fail the assertion?”

Running this example through Kani now returns a “VERIFICATION SUCCESSFUL” result meaning the tool could not find such a choice.

$ cargo kani --harness stretched_rectangle_can_hold_original_fixed

# --snip--

VERIFICATION SUCCESSFUL

Because under the hood, Kani uses techniques based on logic, this is a mathematically rigorous result equivalent to exhaustively testing all possibilities. We just saved ourselves a few billion years of testing! So at this point of our journey, as a result of using automated reasoning techniques, we’re getting assurance about our code that we could not have gotten (in a timely fashion) through dynamic testing.

Of course, it’s equally important to state what assumptions this result relies on.

As is the case for other automated reasoning tools, results from Kani depend on the harness accurately reflecting how the code will be used (such as the assumptions on symbolic variables width and height in the harness above) as well as the correctness of the tool implementation itself and the parts of the system that are not analyzed (such as the hardware that will run the executable).

Understanding these limitations is an important aspect of using automated reasoning tools like Kani that we’ll cover in future posts.

In the meantime, if you’d like to understand more about automated reasoning then check out this Amazon Science blog post, which is a gentle introduction to the topic.

Wrapping up

To summarize, the gap between property-based testing and automated reasoning can be small in some instances, like the example we’ve covered. [In fact, we even see a world where we could write a single harness that could be used for both.] The important distinction is that testing is dynamic (i.e., running the code to find potential bugs), whereas automated reasoning is static (i.e., analyzing the code to, in effect, exhaustively find all potential bugs), so there is a tangible improvement to the level of assurance. This combination of a relatively small change to start using tools like Kani with an outcome of higher assurance is the reason why we’re so excited to be working on this project!

To test drive Kani yourself, check out our “getting started” guide. We have a one-step install process and examples, including all the code in this post with instructions on reproducing the results yourself, so you can try proving your code today.