Using the Kani Rust Verifier on a Firecracker Example

In this post we’ll apply the Kani Rust Verifier (or Kani for short), our open-source formal verification tool that can prove properties about Rust code, to an example from Firecracker, an open source virtualization project for serverless applications. We will use Kani to get a strong guarantee that Firecracker’s block device is correct with respect to a simple virtio property when parsing guest requests, which may be invalid or malicious. In this way, we show how Kani can complement Firecracker’s defense in depth investments, such as fuzzing.

Firecracker is a Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM) for lightweight virtual machines (microVMs). A virtual machine is an abstract compute environment (i.e., a set of resources such as processors, memory and I/O) that is complete enough to run an operating system (also called a guest in this context). A Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM) is a specialized systems component responsible for managing and running virtual machines (in an analogous way to how an operating system would manage and run processes).1

Firecracker was designed to meet the requirements of serverless and container applications, such as AWS Lambda and AWS Fargate. In these applications, the requirements are that multiple customer workloads run on the same hardware with minimal overhead (for efficiency and performance) whilst preserving strong security and isolation.

For a deep dive into the design and implementation of Firecracker, see this NSDI 2020 paper. Firecracker’s design doc gives a description of its internal architecture that suffices for our purposes:

Each Firecracker process encapsulates one and only one microVM. The process runs the following threads: API, VMM and vCPU(s). The API thread is responsible for Firecracker’s API server and associated control plane. It’s never in the fast path of the virtual machine. The VMM thread exposes the machine model, minimal legacy device model, microVM metadata service (MMDS) and VirtIO device emulated Net, Block and Vsock devices, complete with I/O rate limiting. In addition to them, there are one or more vCPU threads (one per guest CPU core).

In this post, we will focus on the requirements for security and isolation for Firecracker’s device emulation code. The central difficulty is that devices must be exposed by Firecracker to a guest (in order for the guest to do useful work) but Firecracker cannot trust the guest to be well-behaved. Firecracker’s design doc says: “from a security perspective, all vCPU threads [running the guest] are considered to be running malicious code as soon as they have been started; these malicious threads need to be contained”. This is important because bugs in code responsible for containment, such as device emulation, are potential security issues. For example, a buffer overflow bug in Firecracker’s vsock device was the root cause of a CVE that could “be used by a malicious guest to read from and write to a segment of the host-side Firecracker process’ heap address space” (source).

One of the select number of devices exposed by Firecracker to the microVM is a block device. (A block device, such as a disk, is a device that allows random access of data in fixed-size blocks.) In Firecracker, the block device is a piece of code that emulates a physical block device from the perspective of the guest, but in reality is a disk image that is specified by the user when setting up the microVM.2 At a high-level, the guest (running on an untrusted vCPU thread) sends read and write requests that must be handled by the device (running on the trusted VMM thread). Informally, a property that we would like high assurance for is that the Firecracker block device behaves as we expect regardless of the request, which is to say, regardless of any untrusted guest behavior. In the next sections we’ll get into more detail about how requests work, what we mean by “behaves as we expect” more precisely, and show how we can use Kani to get this assurance.

Background: virtio requests in Firecracker

This section explains how requests are transferred from the guest to Firecracker (the host).3 If you’re familiar with virtio then feel free to skip ahead.

Firecracker uses a standard interface for virtualized I/O called virtio.4 The main data structures are an array (called a descriptor table) and a ring data structure (called a virtqueue) which are shared between a guest driver and the host’s (emulated) device. At a high-level, the guest allocates buffers that contain data for the device, registers these buffers with a descriptor table, and uses a virtqueue to signal that the buffers are ready to be consumed.

Let’s start with the descriptor table. Each entry of a descriptor table is a descriptor which gives metadata for a single buffer. In Rust, a descriptor is a struct with C layout:

#[repr(C)]

struct Descriptor {

addr: u64,

len: u32,

flags: u16,

next: u16,

}

The addr and len fields give the address and length of a buffer.

The flags field indicates whether the buffer is read-only or write-only from the point of view of the device (a buffer cannot be both readable and writable).

Additionally, if flags indicates that the descriptor is “chained” then the next field gives the index in the descriptor table of the subsequent descriptor.

Descriptor chaining allows multiple buffers to be grouped into a logical list (also known as a scatter/gather list).

The virtio standard does not specify how a request should be chopped up into descriptors/buffers.

However, the Firecracker block device expects that read requests use a descriptor chain of length 3:

- The first describes a read-only buffer that specifies a read request type (

VIRTIO_BLK_T_IN) and the sector to be read (multiplying the sector by the block size, which is 512 bytes for Firecracker, gives the offset). - The second describes a write-only buffer for the device to fill with the contents of the requested sector. The length of this buffer is the requested size.

- The third describes a write-only buffer for the device to fill with a status byte indicating whether the request succeeded.

A write request is similar except that the first buffer specifies a write request type (VIRTIO_BLK_T_OUT) and the second descriptor describes a read-only buffer for the device that contains the data to be written to the requested sector.

The following figure shows a descriptor table with descriptors and buffers for a read request of sector 5 of 2048 bytes.

The descriptor chain begins at index 7 and continues through 12 and 20 and the descriptors point-to buffers at addresses A, B and C, respectively.

Descriptor Table

+---------+----------+--------------+---------+

| | | | |

7 | addr:A | len: 16 | flags:RO|NXT | next:12 |

| ... | | | |

12 | addr:B | len:2048 | flags:WO|NXT | next:20 |

| | | | |

| ... | | | |

| | | | |

20 | addr:C | len: 1 | flags:WO | next:-- |

| | | | |

+---------+----------+--------------+---------+

Buffer 0: read request

+-------------+----------+-----------+

A: | reqtype: IN | reserved | sector: 5 |

+-------------+----------+-----------+

Buffer 1: currently empty, will be filled by device with data

+---------------------------------------- ------+

B: | ... |

+---------------------------------------- ------+

Buffer 2: status byte, will be filled by device to indicate success/failure

+-----------+

C: | status:-- |

+-----------+

Finally, the virqueue is responsible for communicating descriptors between the guest and host. The virtqueue has two rings called the available ring and used ring. The available ring is used by a guest to enqueue the index of the head of a descriptor chain and mark it ready for processing. After the device has dealt with a descriptor chain it enqueues the index to the used ring in order to return the descriptors (and buffers) to the guest. We won’t dive into more details of the virtqueue in this post, such as how the device is notified that there are requests, but this article from IBM gives a deeper explanation.

Importantly, all of the structures we have discussed—virtqueues, descriptor tables and the buffers referred-to by descriptors—reside in guest memory, but are inputs for code executed by Firecracker’s emulation (VMM) thread. This means they are under the control of the guest and so they must be validated by Firecracker.

Let’s pickup what Firecracker must do when it has a request to process.5

Given the index of the head of a descriptor chain (passed to the block device from the available ring) we have to determine whether it encodes a valid request.

The first step is to read the raw descriptor and lift it into a DescriptorChain (or return an error).6

As well as storing the descriptor’s basic attributes (i.e., address and length), a DescriptorChain also has a method next which returns the next descriptor in the chain (if the descriptor specifies a next).

/// A virtio descriptor chain.

pub struct DescriptorChain<'a> {

desc_table: GuestAddress,

queue_size: u16,

ttl: u16, // used to prevent infinite chain cycles

/// Reference to guest memory

pub mem: &'a GuestMemoryMmap,

/// Index into the descriptor table

pub index: u16,

/// Guest physical address of device specific data

pub addr: GuestAddress,

/// Length of device specific data

pub len: u32,

/// Includes next, write, and indirect bits

pub flags: u16,

/// Index into the descriptor table of the next descriptor if flags has

/// the next bit set

pub next: u16,

}

impl<'a> DescriptorChain<'a> {

fn checked_new(

mem: &GuestMemoryMmap,

desc_table: GuestAddress,

queue_size: u16,

index: u16,

) -> Option<DescriptorChain> {

// --snip--

// read the appropriate index of the descriptor table to get a Descriptor

// validate the descriptor and return a new DescriptorChain

}

/// Gets the next descriptor in this descriptor chain, if there is one.

pub fn next_descriptor(&self) -> Option<DescriptorChain<'a>> {

// --snip--

}

}

The next step is to parse DescriptorChain into a Request.

This will traverse the descriptor chain and buffers to determine whether the request is valid (and return an error otherwise).

The parameter avail_desc is a valid DescriptorChain.

The parameter mem encapsulates Firecracker’s access to memory shared with the guest.7

This gives methods for reading and writing objects with bounds checks.

Finally, the parameter num_disk_sectors is the number of sectors (512-byte blocks) of the underlying disk image.

pub struct Request {

pub r#type: RequestType, // i.e., In (read) | Out (write) | ...

pub data_len: u32,

pub status_addr: GuestAddress,

sector: u64,

data_addr: GuestAddress,

}

impl Request {

pub fn parse(

avail_desc: &DescriptorChain,

mem: &GuestMemoryMmap,

num_disk_sectors: u64,

) -> result::Result<Request, Error> {

// --snip--

// traverse the descriptor chain expecting 3 descriptors for reads/writes and perform validity checks such as the first buffer must be read-only.

}

}

A property of interest

There are many properties that we might want to show about parse.

Let’s start with a simple one from the virtio specification.

2.6.4.2 Driver Requirements: Message Framing

The driver MUST place any device-writable descriptor elements after any device-readable descriptor elements.

This is a requirement on the driver under the control of the guest.

However, Firecracker cannot trust that this is the case: the requirement has to be validated.

Here’s how we can turn it into a requirement on the parse method: it must be the case that if parse succeeds (i.e., returns Ok(...)) then the message framing requirement was met (and, also, if the requirement is not met then parse must fail).

Note that it is acceptable for the parse method to fail even if this requirement is met.

For example, a descriptor chain may be properly message framed, but specify an invalid request type.

Imagine for a moment that we had a checker that could tell us whether the sequence of Descriptors returned by mem adhered to this requirement.

Then we could write:

let result = Request::parse(/*--snip--*/);

if result.is_ok() {

assert!(checker.virtio_2642_holds())

}

if !checker.virtio_2642_holds() {

assert!(result.is_err());

}

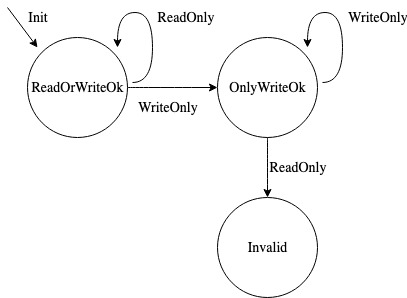

Here’s one way to implement the checker.

The idea is to use a finite-state machine that moves when we see a new permission.

We start in a state ReadOrWriteOk where seeing a read-only or write-only descriptor is valid.

When we see a write-only descriptor we move to a new state OnlyWriteOk where only further write-only descriptors are valid.

If we see a read-only descriptor in this new state then we have invalidated the requirement.

Implementing virtio_2642_holds is as simple as testing whether the state is not Invalid.

#[derive(std::cmp::PartialEq, Clone, Copy)]

enum State {

ReadOrWriteOk,

OnlyWriteOk,

Invalid,

}

/// State machine checker for virtio requirement 2.6.4.2

pub struct DescriptorPermissionChecker {

state: State,

}

impl DescriptorPermissionChecker {

pub fn new() -> Self {

DescriptorPermissionChecker {

state: State::ReadOrWriteOk,

}

}

pub fn update(&mut self, next_permission: DescriptorPermission) {

let next_state = match (self.state, next_permission) {

(State::ReadOrWriteOk, DescriptorPermission::WriteOnly) => State::OnlyWriteOk,

(State::OnlyWriteOk, DescriptorPermission::ReadOnly) => State::Invalid,

(_, _) => self.state,

};

self.state = next_state;

}

pub fn virtio_2642_holds(&self) -> bool {

self.state != State::Invalid

}

}

Using Kani

Caveats

This example has a number of simplifications.

In particular, we took the block implementation from Firecracker v1.0 and pulled it into a set of independent files so that we could focus on the verification rather than how Kani integrates into a large project.

Anywhere that we’ve simplified we’ve marked it with a comment Kani change.

Our example is available in Kani’s test directory with instructions on reproducing the results of this post (see Further Reading).

Using kani::any::<T>() to mock guest memory

In earlier posts (here and here) we introduced Kani any<T>().

This is a feature that informally generates “any T value”.

This is not the same as a randomly chosen concrete value (as in fuzzing) but rather a symbolic value that represents any possible value of the appropriate type.

The key idea is that we can use any in a Kani harness to verify the behavior of our code with respect to all possible values of an input (rather than having to exhaustively enumerate them).

In previous posts, we’ve mostly used any in proof harnesses (the entry point for analysis analogous to a test in unit testing).

We’ll go a bit further here.

When we look at the parse method, a good place to think about using any is the guest memory mem.

This is because Firecracker cannot make assumptions about the values returned from reading, which is a good match for symbolic values.

By writing a verification-version mock of GuestMemoryMmap we will be able to verify the behavior of parse with respect to any data returned by reading guest memory.

Of course, it is important to say that this means we will not be verifying the implementation of GuestMemoryMmap itself.

The most important method for us to implement in our mock is read_obj.

This is a generic method defined for ByteValued types.

The unsafe trait ByteValued signifies that it is safe to initialize a value of type T with contents from a byte array.

For example, this is true for the Descriptor type as it is composed only of integer types.

The method takes a GuestAddress (a newtype’d u64) and returns either a value of type T initialized with the contents at this address or an error.

Here’s how we can use any to mock read_obj.

The first use is a symbolic boolean to model both returning a successful (symbolic) value and the error case.

In the successful case, we generate a symbolic value val of type T to model reading memory (we will defer the discussion of check_on_read_val for now).

In the error case, we generate a symbolic value of type Error.

This is an enum that includes guest memory errors such as requesting an invalid address.

The intention of our mock is to enable Kani to explore the behavior of a caller of read_obj (like parse) under any of these possibilities.

fn read_obj<T>(&self, addr: GuestAddress) -> Result<T, Error>

where

T: ByteValued + kani::Arbitrary + ReadObjChecks<T>,

{

if kani::any() {

let val = kani::any::<T>();

T::check_on_read_val(&self, &val);

Ok(val)

} else {

Err(kani::any::<Error>())

}

}

Now let’s address the ReadObjChecks trait bound that we added, which allows us to call T::check_on_read_val where we pass in the generated symbolic value.

This allows us to attach our checker to calls of read_obj where T = Descriptor.

In this way, we can update our state machine.

trait ReadObjChecks<T> {

type CheckerType;

fn check_on_read_val(mem: &GuestMemoryMmap, read_val: &T);

}

impl ReadObjChecks<Descriptor> for Descriptor {

type CheckerType = DescriptorPermissionChecker;

fn check_on_read_val(mem: &GuestMemoryMmap, read_val: &Descriptor) {

let current_permission = DescriptorPermission::from_flags(read_val.flags);

mem.permission_checker

.borrow_mut()

.update(current_permission);

}

}

Proof harness

Putting this all together, we can write a harness as follows.

At a high-level, we generate symbolic inputs for the parse and then assert our property of interest.

The only nit is that we must generate an initial valid DescriptorChain (not all kani::any::<DescriptorChain>() values are valid).

The way we chose to do this is to call DescriptorChain::checked_new with symbolic inputs and proceed if this returns a valid DescriptorChain.

#[cfg(kani)]

mod verification {

use super::*;

#[kani::proof]

pub fn requirement_2642() {

let mem = GuestMemoryMmap::new();

let desc_table: GuestAddress = kani::any();

let queue_size: u16 = kani::any();

let index: u16 = kani::any();

let desc = DescriptorChain::checked_new(&mem, desc_table, queue_size, index);

match desc {

Some(x) => {

let req = Request::parse(&x, &mem, kani::any::<u64>());

if req.is_ok() {

assert!(mem.permission_checker.borrow().virtio_2642_holds());

}

if !(mem.permission_checker.borrow().virtio_2642_holds()) {

assert!(req.is_err());

}

}

None => {}

};

}

}

Passing the harness to Kani results in VERIFICATION:- SUCCESSFUL in a few seconds.

As sanity check, if we insert an issue such as forgetting a validity check to ensure the third buffer is write-only, then Kani reports an error (since in this case it is possible to fail virtio requirement 2.6.4.2 but return a valid Request).

Our example is available in Kani’s test directory with instructions on reproducing these results.

But what does this result mean?

A way to approximate the power of this approach is to think about the number of test cases we would need to write to get the same level of assurance.

Ignoring error cases, which are also covered, our harness using our mock guest memory enables Kani to explore the behavior of parse when it reads up to 3 symbolic descriptors.

These are each 16-byte values.

The parse function also reads the first buffer to determine the request type and sector.

This is a 16-byte value.

In this case that’s (2^8)^16 * (2^8)^16 * (2^8)^16 * (2^8)^16 = 2^512 test cases.

Kani allows us to definitively check a property of interest (if virtio requirement 2.6.4.2 does not hold then parse will fail) across all of these cases.

Summary

In this post, we introduced Firecracker and focused our attention on its virtio block device implementation.

We encoded a finite-state machine to check a simple virtio property.

Using Kani’s verification features, in particular, kani::any::<T>(), we built a mock guest memory that uses symbolic values to model reads (of any value).

Finally, we brought this all together into a proof harness that Kani can analyze in seconds even though writing all the possible test cases would be prohibitively expensive.

To test drive Kani yourself, check out our “getting started” guide. We have a one-step install process and examples, including all the code in this post with instructions on reproducing the results yourself, so you can try proving your code today.

Look out for a follow up post where we’ll use Kani on an example from Tokio.

Further Reading

- Firecracker project

- Firecracker NSDI 2020 paper

- Firecracker’s design doc

- Code and instructions for reproducing the results in this post

Footnotes

-

Virtualization is an area with conflicting and overlapping definitions. In this post we’ve followed the terminology from Firecracker’s NSDI 2020 paper. For more, check out “Hardware and Software Support for Virtualization” (Bugnion, Nieh and Tsafrir). ↩

-

For an example of setting up and running a Firecracker microVM using Firecracker’s REST API, check out Jeff Barr’s AWS blog post. ↩

-

Firecracker uses the Linux Kernel Virtual Machine (KVM) to delegate resource allocation (such as CPU scheduling and memory management) to a “host” operating system. This is known as a type-2 virtualization. LWM.net has a great intro to KVM. ↩

-

For more about virtio see the specification. ↩

-

We will be exploring the implementation code in

src/devices/src/virtio. Processing of requests for the block device begins here. ↩ -

See https://github.com/firecracker-microvm/firecracker/blob/3e217c19abaea275138ac13a4be0f85b834ec246/src/devices/src/virtio/queue.rs#L64 ↩

-

As a KVM-based VMM, Firecracker can allocate guest memory using

mallocormmapand have it be mapped into the physical address space of the guest. ↩