Using Kani to Validate Security Boundaries in AWS Firecracker

Security assurance is paramount for any system running in the cloud. In order to achieve the highest levels of security, we have applied the Kani model checker to verify safety-critical properties in core components of the Firecracker Virtual Machine Monitor using mathematical logic.

Firecracker is an open source project written in Rust which uses the Linux Kernel-based Virtual Machine (KVM) to create and manage microVMs. Firecracker has a minimalist design which allows fast (~150ms) microVM start-up time, secure multi-tenancy of microVMs on the same host and memory/CPU over-subscription. Firecracker is currently used in production by AWS Lambda, AWS Fargate and parts of AWS Analytics to build their service platforms.

For the past 7 months, Felipe Monteiro, an Applied Scientist on the Kani team and Patrick Roy, a Software Development Engineer from the AWS Firecracker team, collaborated to develop Kani harnesses for Firecracker. As a result of this collaboration, the Firecracker team is now running 27 Kani harnesses across 3 verification suites in their continuous integration pipelines (taking approximately 15 minutes to complete), ensuring that all checked properties of critical systems are upheld on every code change.

In this blog post, we show how Kani helped Firecracker harden two core components, namely our I/O rate limiter and I/O transport layer (VirtIO), presenting the issues we were able to identify and fix. Particularly, the second part of this post picks up from a previous Kani/Firecracker blogpost and shows how improvements to Kani over the last year made verifying conformance with a section of the VirtIO specification feasible.

Noisy-Neighbor Mitigations via Rate Limiting

In multi-tenant systems, microVMs from different customers simultaneously co-exist on the same physical host. We thus need to ensure that access to host resources, such as disk and network, is shared fairly. We should not allow a single “greedy” microVM to transfer excessive amounts of data from disk to the point where other microVMs’ disk access gets starved off (a “noisy neighbor” scenario). Firecracker offers a mitigation for this via I/O rate-limiting. From the documentation:

Firecracker provides VirtIO/block and VirtIO/net emulated devices, along with the application of rate limiters to each volume and network interface to make sure host hardware resources are used fairly by multiple microVMs. These are implemented using a token bucket algorithm […]

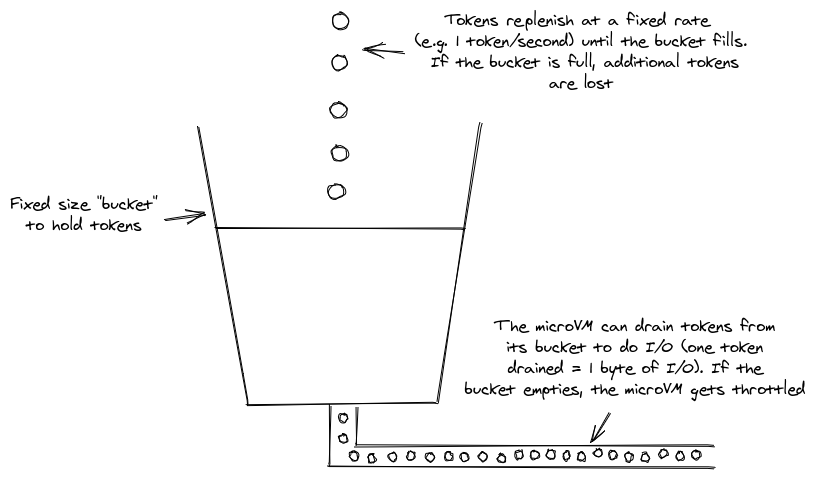

In a token bucket based rate-limiter, each microVM has a budget of “tokens” that can be exchanged for permission to do one byte of I/O. These tokens regenerate at a fixed rate, and if the microVM runs out of tokens, it gets I/O-throttled. This process of draining and replenishing is best visualized by an actual bucket into which water drips at a fixed rate, and from which water can be extracted at some limited rate:

The property we want to verify is that a microVM is not allowed to exceed the configured maximum I/O throughput rate. For a virtual block device rate-limited at 1GB/s, we want to prove that in any one-second interval, at most 1GB of data is allowed to pass through the device.

What sounds simple in theory is actually fairly difficult to implement. For example, due to a rounding error a guest could, in some scenarios, do up to 0.01% more I/O than configured. We discovered this bug thanks to a Kani harness for our throughput property stated above, and this harnesses is the main focus of the rest of this section.

Teaching Kani about Time

The core component of our rate-limiting implementation is a TokenBucket. In Firecracker, we define it as

pub struct TokenBucket {

// Maximal number of tokens this bucket can hold.

size: u64,

// Complete refill time in milliseconds.

refill_time: u64,

// Current token budget.

budget: u64,

// Last time this token bucket was replenished.

last_update: Instant,

// -- snip --

}

It offers an auto_replenish function which computes how many tokens the leaky bucket algorithm should have generated since last_update (and then updates last_update accordingly). This function will be the target of our verification.

A TokenBucket is inherently tied to time-related APIs such as std::time::Instant, for which Kani does not have built-in support. This means it is not able to reason about TokenBuckets. To solve this problem, we use Kani’s stubbing to provide a model for the Instant::now function. Since Firecracker uses a monotonic clock for its rate-limiting, this stub needs to return non-deterministic monotonically non-decreasing instants.

However, when trying to stub now, one will quickly notice that Instant does not offer any constructors for creating an instance from, say, a Unix timestamp. In fact, it is impossible to construct an Instant outside of the standard library as its fields are private. When in such a situation, the solution is often to go down the call stack of the function that you want to stub, to see if any of the functions further down can be stubbed out instead to achieve the desired effect. In our case, now calls functions in (private) OS-specific time modules, until it bottoms out at libc::clock_gettime.

The clock_gettime function is passed a pointer to a libc::timespec structure, and the tv_sec and tv_nsec members of this structure are later used to construct the Instant returned by Instant::now. Therefore, we can use the following stub to achieve our goal of getting non-deterministic, monotonically non-decreasing Instants:

mod stubs {

static mut LAST_SECONDS: i64 = 0;

static mut LAST_NANOS: i64 = 0;

const NANOS_PER_SECOND: i64 = 1_000_000_000;

pub unsafe extern "C" fn clock_gettime(_clock_id: libc::clockid_t, tp: *mut libc::timespec) -> libc::c_int {

unsafe {

// kani::any_where provides us with a non-deterministic number of seconds

// that is at least equal to LAST_SECONDS (to ensure that time only

// progresses forward).

let next_seconds = kani::any_where(|&n| n >= unsafe { LAST_SECONDS });

let next_nanos = kani::any_where(|&n| n >= 0 && n < NANOS_PER_SECOND);

if next_seconds == LAST_SECONDS {

kani::assume(next_nanos >= LAST_NANOS );

}

(*tp).tv_sec = LAST_SECONDS;

(*tp).tv_nsec = LAST_NANOS;

LAST_SECONDS = next_seconds;

LAST_NANOS = next_nanos;

}

0

}

}

Note how the first invocation of this stub will always set tv_sec = tv_nsec = 0, as this is what the statics are initialized to. This is an optimization we do because the rate-limiter only cares about the delta between two instants, which will be non-deterministic as long as one of the two instants is non-deterministic. In order to keep Kani performant, it is important to minimize the number of non-deterministic values, especially if multiplication and division are involved.

Using this stub, we can start writing a harness for auto_replenish such as

#[kani::proof]

#[kani::unwind(1)] // Enough to unwind the recursion at `Timespec::sub_timespec`.

#[kani::stub(libc::clock_gettime, stubs::clock_gettime)]

fn verify_token_bucket_auto_replenish() {

// Initialize a non-determinstic `TokenBucket` object.

let mut bucket: TokenBucket = kani::any();

bucket.auto_replenish();

// is_valid() performs sanity checks such as "budget <= size".

// It is the data structure invariant of `TokenBucket`.

assert!(bucket.is_valid());

}

Let us now see how we can extend this harness to allow us to verify that our rate limiter is replenishing tokens at exactly the requested rate.

Verifying our Noisy-Neighbor Mitigation

Our noisy neighbor mitigation is correct if we always generate the “correct” number of tokens with each call to auto_replenish, meaning it is impossible for a guest to do more I/O than configured. Formally, this means

Here, $new\_tokens$ is the number of tokens that auto_replenish generated. The fraction $\left(\frac{refill\_time}{size}\right)$ is simply the time it takes to generate a single token. Thus, the property states that if we compute the time that it should have taken to generate $new\_tokens$ and subtract it from the time that actually passed, we are left with an amount of time less than what it would take to generate an additional token: we replenished the maximal number of tokens possible.

The difficulty of implementing a correct rate limiter is dealing with “leftover” time: If enough time passed to generate “1.8 tokens”, what does Firecracker do with the “0.8” tokens it cannot (as everything is integer valued) add to the budget? Originally, the rate limiter simply dropped these: if you called auto_replenish at an inopportune time, then the “0.8” would not be carried forward and the guest essentially “lost” part of its I/O allowance to rounding. Then, with #3370, we decided to fix this by only advancing $last\_update$ by $new\_tokens \times \left(\frac{refill\_time}{size}\right)$ instead of setting it to now. This way the fractional tokens will be carried forward, and we even hand-wrote a proof to check that $last\_update$ and the actual system time will not diverge, boldly concluding

This means that $last\_updated$ indeed does not fall behind more than the execution time of

auto_replenishplus a constant dependent on the bucket configuration.

Here, the “constant dependent on the bucket configuration” was $\left(\frac{refill\_time}{size}\right)$, rounded down. This is indeed implies our above specified property, so when we revisited auto_replenish a few months later to add the following two debug_asserts! derived from our formal property.

// time_adjustment = tokens * (refill_time / size)

debug_assert!((now - last_update) >= time_adjustment);

// inequality slightly rewritten to avoid division

debug_assert!((now - last_update - time_adjustment) * size < refill_time);

we expected the verification to succeed. However, Kani presented us with The “VERIFICATION FAILED” message, which was unexpected to say the least.

So what went wrong? In the hand-written proof, the error was assuming that $-\lfloor -x \rfloor = \lfloor x \rfloor$ (had this step been gotten correctly, the bound would have been $\left(\frac{refill\_time}{size}\right)$ rounded up, which obviously allows for violations). To see how our code actually violates the property, we need to have a look at how the relevant part of auto_replenish was actually implemented:

let time_delta = self.last_update.elapsed().as_nanos() as u64;

// tokens = time_delta / (refill_time / size) rewritten to not run into

// integer division issues.

let tokens = (time_delta * self.size) / self.refill_time;

let time_adjustment = (tokens * self.refill_time) / self.size

self.last_update += Duration::from_nanos(time_adjustment);

The issue lies in the way we compute time_adjustment: Consider a bucket of size 2 with refill time 3ns and assume a time delta of 11ns. We compute $11 \times 2/3 \approx 7$ tokens, and then a time adjustment of $7 \times 3/2 \approx 10ns$. However, 10ns is only enough to replenish $10 \times 2/3 \approx 6$ tokens! The problem here is that 7 tokens do not take an integer number of nanoseconds to replenish. They take 10.5ns. However the integer division rounds this down, and thus the guest essentially gets to use those 0.5ns twice. Assuming the guest can time when it triggers down to nanosecond precision, and the rate limiter is configured such that $\left(\frac{refill\_time}{size}\right)$ is not an integer, the guest could theoretically cause these fractional nanoseconds to accumulate to get an extra token every $10^{6} \times \left(\frac{refill\_time}{size}\right) \times max\left(1, \left(\frac{refill\_time}{size}\right)\right)$ nanoseconds. For a rate limiter configured at 1GB/s, this would be an excess of 1KB/s.

The fix for this was to round up instead of down in our computation of time_adjustment. For the complete code listing of the rate limiter harnesses, see here.

Conformance to the VirtIO Specification

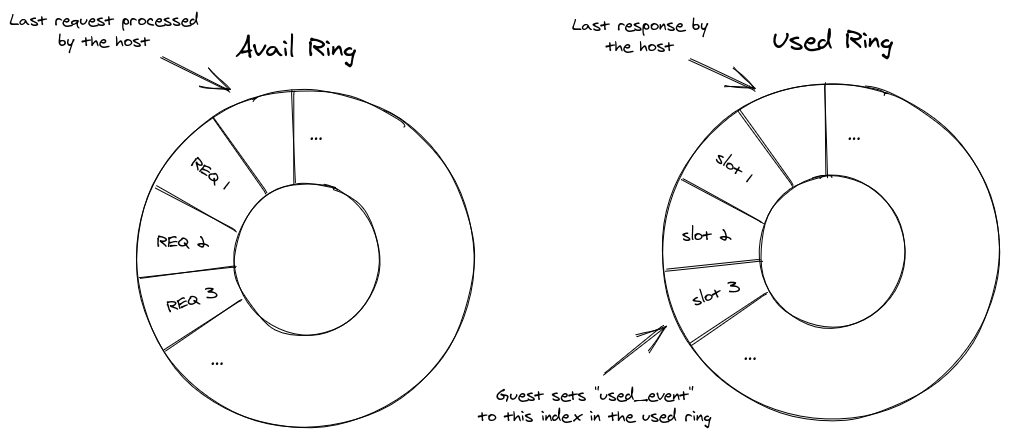

Firecracker is a para-virtualization solution, meaning the guest is aware that it is running inside of a virtual machine. This allows host and guests to collaborate when it comes to I/O, as opposed to the host having to do all the heavy lifting of emulating physical devices. Firecracker uses VirtIO for the transport-layer protocol of its paravirtualized device stack. It allows the guest and host to exchange messages via pairs of ring buffers called a queue. At a high level, the guest puts requests into a shared array (the “descriptor table”) and puts the index into the descriptor table at which the host can find the new request into the request ring (the “avail ring” in VirtIO lingo). It then notifies the host via interrupt that a new request is available for processing. The host now processes the request, updating the descriptor table entry with its response and, upon finishing, writes the index into the descriptor table into a response ring (the “used ring”). It then notifies the guest that processing of a request has finished.

The Firecracker side of this queue implementation sits right at the intersection between guest and host. According to Firecracker’s threat model:

From a security perspective, all vCPU threads are considered to be running untrusted code as soon as they have been started; these untrusted threads need to be contained.

The entirety of the VirtIO queue lives in shared memory and can thus be written to by the vCPU threads. Therefore, Firecracker cannot make any assumptions about its contents. In particular, it needs to operate securely no matter the memory content. For anyone who has worked with Kani before, this yearns for a generous application of kani::vec::exact_vec, which generates a fixed size vector filled with arbitrary values. We can set up an area of non-deterministic guest memory as follows:

fn arbitrary_guest_memory() -> GuestMemoryMmap {

// We need ManuallyDrop to "leak" the memory area to ensure it lives for

// the entire duration of the proof.

let memory = ManuallyDrop::new(kani::vec::exact_vec::<u8, GUEST_MEMORY_SIZE>())

.as_mut_ptr();

let region = unsafe {

MmapRegionBuilder::new(GUEST_MEMORY_SIZE)

.with_raw_mmap_pointer(memory)

.build()

.unwrap()

};

let guest_region = GuestRegionMmap::new(region, GuestAddress(0)).unwrap();

// Use a single memory region, just as Firecracker does for guests of size < 2GB.

// For largest guests, Firecracker uses two regions (due to the MMIO gap being

// at the top of 32-bit address space).

GuestMemoryMmap::from_regions(vec![guest_region]).unwrap()

}

Note that this requires a stub for libc::sysconf, which is used by .build() to verify that guest memory is correctly aligned. We can use a stub that always returns 1, which causes vm_memory to consider all pointers to be correctly aligned.

With our non-deterministic guest memory setup, we can start verifying things! On the host side, a queue is just a collection of guest physical addresses. We currently cannot set all of them to non-deterministic values, as the complexity of our mathematical model would explode, but we can get fairly far:

impl kani::Arbitrary for Queue {

fn any() -> Queue {

// Firecracker statically sets the maximal queue size to 256.

let mut queue = Queue::new(FIRECRACKER_MAX_QUEUE_SIZE);

const QUEUE_BASE_ADDRESS: u64 = 0;

// Descriptor table has 16 bytes per entry, avail ring starts right after.

const AVAIL_RING_BASE_ADDRESS: u64 =

QUEUE_BASE_ADDRESS + FIRECRACKER_MAX_QUEUE_SIZE as u64 * 16;

// Used ring starts after avail ring (which has size 6 + 2 * FIRECRACKER_MAX_QUEUE_SIZE),

// and needs 2 bytes of padding.

const USED_RING_BASE_ADDRESS: u64 =

AVAIL_RING_BASE_ADDRESS + 6 + 2 * FIRECRACKER_MAX_QUEUE_SIZE as u64 + 2;

queue.size = FIRECRACKER_MAX_QUEUE_SIZE;

queue.ready = true;

queue.desc_table = GuestAddress(QUEUE_BASE_ADDRESS);

queue.avail_ring = GuestAddress(AVAIL_RING_BASE_ADDRESS);

queue.used_ring = GuestAddress(USED_RING_BASE_ADDRESS);

// Index at which we expect the guest to place its next request into

// the avail ring.

queue.next_avail = Wrapping(kani::any());

// Index at which we will put the next response into the used ring.

queue.next_used = Wrapping(kani::any());

// Whether notification suppression is enabled for this queue.

queue.uses_notif_suppression = kani::any();

// How many responses were added to the used ring since the last

// notification was sent to the guest.

queue.num_added = Wrapping(kani::any());

queue

}

}

Here, the final two fields, uses_notif_suppression and num_added are relevant for the property we want to verify. Notification suppression is a mechanism described in Section 2.6.7 of the VirtIO specification which is designed to reduce the overall number of interrupts exchanged between guest and host. When enabled, it allows the guest to tell the host that it should not send an interrupt for every single processed request, but instead wait until a specific number of requests have been processed. The guest does this by writing a used ring index into a predefined memory location. The host then will not send interrupts until it uses the specified index for a response.

To better understand this mechanism, consider the following queue:

The guest just wrote requests 1 through 3 into the avail ring and notified the host. Without notification suppression, the host would now process request 1, write the result into slot 1, and notify the guest about the first request being done. With notification suppression, the host will instead realize that the guest does not want notification until it writes a response to the third slot. This means the host will only notify the request after processing all three requests, and we saved ourselves two interrupts.

This is a much simplified scenario. The exact details of this are written down in Section 2.6.7.2 of the VirtIO 1.1 specification. We can turn that specification into the following Kani harness:

#[kani::proof]

#[kani::unwind(2)] // Guest memory regions are stored in a BTreeMap, which

// employs binary search resolving guest addresses to

// regions. We only have a single region, so the search

// terminates in one iteration.

fn verify_spec_2_6_7_2() {

let mem = arbitrary_guest_memory();

let mut queue: Queue = kani::any();

// Assume various alignment needs are met. Every function operating on a queue

// has a debug_assert! matching this assumption.

kani::assume(queue.is_layout_valid(&mem));

let needs_notification = queue.prepare_kick(&mem);

if !queue.uses_notif_suppression {

// After the device writes a descriptor index into the used ring:

// – If flags is 1, the device SHOULD NOT send a notification.

// – If flags is 0, the device MUST send a notification.

// flags is the first field in the avail_ring, which we completely ignore. We

// always send a notification, and as there only is a SHOULD NOT, that is okay

assert!(needs_notification);

} else {

// next_used - 1 is where the previous descriptor was placed.

// queue.used_event(&mem) reads from the memory location at which the guest

// stores the index for which it wants to receive the next notification.

if queue.used_event(&mem) == queue.next_used - Wrapping(1) && queue.num_added.0 > 0 {

// If the idx field in the used ring (which determined where that descriptor index

// was placed) was equal to used_event, the device MUST send a notification.

assert!(needs_notification)

}

// The other case is handled by a "SHOULD NOT send a notification" in the spec.

// So we do not care.

}

}

Beyond these specification conformance harnesses, we also have standard “absence of panics” harnesses, which led us to discover an issue in our code which validates the in-memory layout of VirtIO queues. A guest could trigger a panic in Firecracker by placing the starting address for a VirtIO queue component into the MMIO gap.

Conclusion

Thanks to Kani, the Firecracker team was able to verify critical areas of code that were intractable to traditional methods. These include our noisy-neighbor mitigation, a rate limiter, where interactions with the system clock resulted in traditional testing being unreliable, as well as our VirtIO stack, where the interaction with guest memory lead to a state space impossible to cover by other means.

We found 5 bugs in our rate limiter implementation, the most significant one a rounding error that allowed guests to exceed their prescribed I/O bandwidth by up to 0.01% in some cases. Additionally, we found one bug in our VirtIO stack, where a untrusted guest could set up a virtio queue that partially overlapped with the MMIO memory region, resulting in Firecracker crashing on boot. Finally, the debug assertions added to the code under verification allowed us to identify a handful of unit tests which were not set up correctly. These have also been fixed.

All in all, Kani proof harnesses has proven a valuable defense-in-depth measure for Firecracker, nicely complementing our existing testing infrastructure. We plan to continue our investment in these harnesses as we develop new Firecracker features, to ensure consistently high security standards. To learn more about Kani, check out the Kani tutorial and our previous blog posts.