How Kani helped find bugs in Hifitime

Kani is a verification tool that can help you systematically test properties about your Rust code. To learn more about Kani, check out the Kani tutorial and our previous blog posts.

Hifitime is a scientifically accurate time management library that provides nanosecond precision of durations and time computations for 65 thousand centuries in most time scales (also called time systems). It is useful wherever a monotonic clock is needed, even in the presence of leap second or remote time corrections (like for Network Time Protocol or Precise Time Protocol). It is suitable for desktop applications and for embedded systems without a floating point unit (FPU). It also supports the typical features of date time management libraries, like the formatting and parsing of date times in a no-std environment using the typical C89 tokens, or a human friendly approximation of the difference between dates. For scientific and engineering applications, it is mostly tailored to astronomy (with the inclusion of the UT1 time scale), astrodynamics (with the ET and TDB time scales), and global navigation satellite systems (with the GPS, Galileo, and BeiDou time scales).

The purpose of this blog post is to show how Kani helped solve a number of important non-trivial bugs in hifitime. For completeness’ sake, let’s start with an introduction of the notion of time, how hifitime avoids loss of precision, and finally why Kani is crucial to ensuring the correctness of hifitime.

This is our first blog post from an external contributor. We are very excited for this contribution and thank Christopher Rabotin for his time, interest, and copacetic use of Kani.

Why time matters

Time is just counting subdivisions of the second, it’s a trivial and solved problem. Well, it’s not quite trivial, and often incorrectly solved.

As explained in “Beyond Measure” by James Vincent, measuring the passing of time has been important for societies for millennia. From using the flow of the Nile River to measure the passage of a year, to tracking the position of the Sun in the sky to delimit the start and end of a day, the definition of the time has changed quite a bit.

On Earth, humans follow a local time, which is supposed to be relatively close to the idea that noon is when the Sun is at its height in the sky for the day. We’ve also decided that the divisions of time must be fixed: for example, an hour lasts 3600 seconds regardless of whether it’s 1 am or 2 pm. If we only follow this fixed definition of an hour, then time drifts because the Earth does not in fact complete a full rotation on itself in exactly 24 hours (nor in one sidereal day of 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.091 seconds, which is also an approximation of the UT1 time scale). For “human time” (Universal Coordinated Time, UTC) to catch up with the time with respect to the stars (UT1), we regularly introduce “leap seconds.” Like leap years, where we introduce an extra day every fourth year (with rare exceptions), leap seconds introduce an extra second every so often, as announced by the IERS. When scientists report to the IERS that the Earth is about to drift quite a bit compared to UTC, IERS announces that on a given day at least six months in the future, there will be an extra second in that day to allow for the rotation of the Earth to catch up. In practice, this typically means that UTC clocks “stop the counting of time” for one second. In other words, UTC is not a continuous time scale: that second we didn’t count in UTC still happened for the universe! As the Standards Of Fundamental Astronomy (SOFA) eloquently puts it:

Leap seconds pose tricky problems for software writers, and consequently there are concerns that these events put safety-critical systems at risk. The correct solution is for designers to base such systems on TAI or some other glitch-free time scale, not UTC, but this option is often overlooked until it is too late. – “SOFA Time Scales and Calendar Tools”, Document version 1.61, section 3.5.1

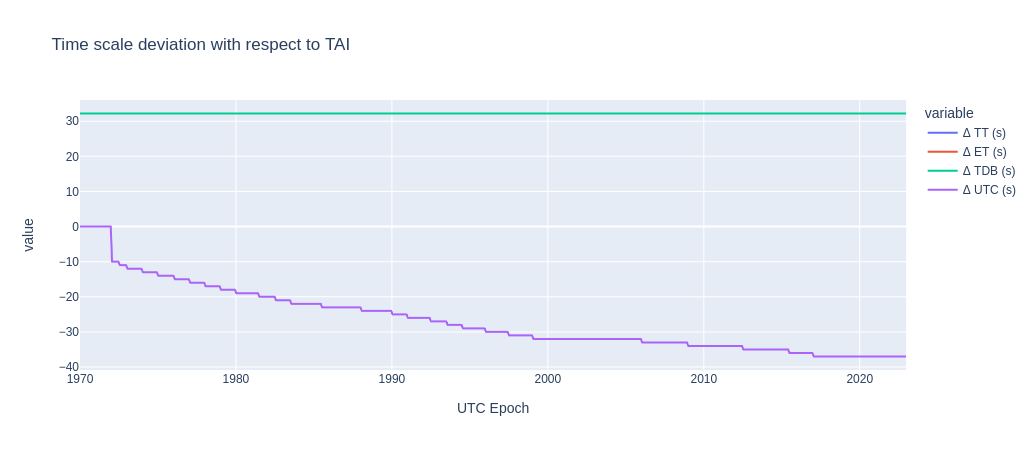

As seen in the figure below, the deviation of the UTC time scale compared to the other time scales increases over time. Moreover, the time between two corrections is not equally spaced. In other words, UTC is not a monotonic clock and attempting to use UTC over a leap second adjustment will cause problems.

Luckily there are a few glitch-free time scales to choose from. Hifitime uses TAI, the international atomic time. This allows quick synchronization with UTC time because both UTC and TAI “tick” at the same rate as they are both Earth based time scales. In fact, with general relativity, we understand that time is affected by gravity fields. This causes the additional problem that a second does not tick with the same frequency on Earth as it does in the vacuum between Mars and Jupiter (which is more than twice as far apart as Mars is from the Sun by the way). As such, the position of planets published by NASA JPL are provided in a time scale in which the influence of the gravity of Earth has been removed and where the “ticks” of one second are fixed at the solar system barycenter: the Dynamic Barycentric Time (TDB) time scale. As you may imagine, this causes lots of problems when converting from human time to any astronomical time.

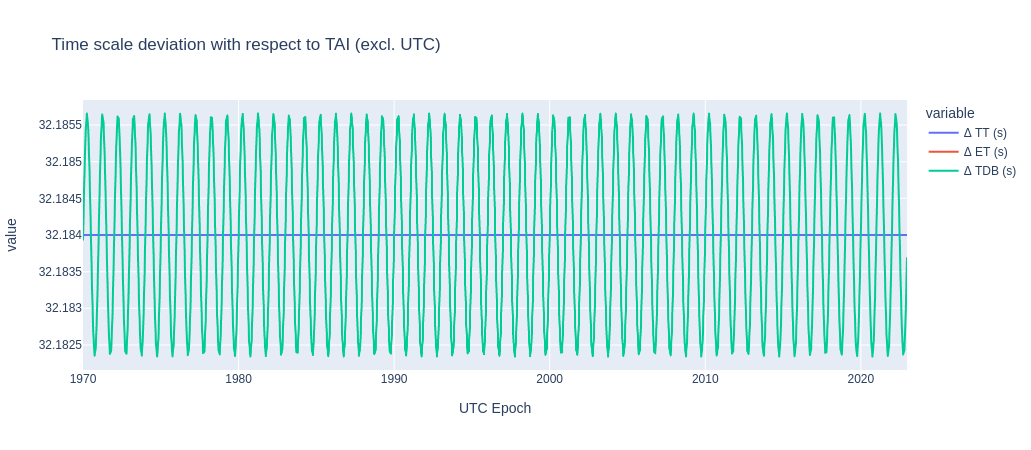

The figure below shows how the effect of gravity on the duration of a second compared to Earth based clocks, like TT (blue line fixed at 32.184 s) and TAI (reference Earth time, not shown since it would be a line at exactly zero).

Avoiding loss of precision

The precision of a floating point value depends on its magnitude (as represented by the exponent) and on how it was computed from other values (rounding modes, error accumulation, use of extended precision for intermediate computations in CPU, etc.). Moreover, some microcontrollers do not have a floating point unit (FPU), meaning that any floating point operation is emulated through software, adding a considerable number of CPU cycles for any computation.

Dates, or “epochs,” are simply the duration past a certain reference epoch. Operations on these epochs, like adding 26.7 days, will cause rounding errors (even sometimes in a single operation like on this f32).

Time scales have different reference epochs, and to correctly convert between different time scales, we must ensure that we don’t lose any precision in the computation of these offsets. That’s especially important given that one of the most common scale in astronomy is the Julian Date, whose reference epoch is 4713 BC (or -4712). Storing such a number with an f64 would lead to very large rounding errors.

SOFA solves this by using a tuple of double precision floating point values for all computations, an approach used in hifitime version 2 but discarded in version 3. In fact, to avoid loss of precision, hifitime stores all durations as a tuple of the number of centuries and the number of nanoseconds into this century. For example (0, 1) is a duration of one nanosecond. Then, the Epoch is a structure containing the TAI duration since the TAI reference epoch of 01 January 1900 at noon and the time scale in which the Epoch was initialized. This approach guarantees no more and no less than one nanosecond of precision on all computations for 32,768 centuries on either side of the reference epoch. (And maybe hifitime should be even more precise?)

Importance of Kani in hifitime

The purpose of hifitime is to convert between time scales, and these drift apart from each other. Time scales are only used for scientific computations, so it’s important to correctly compute the conversion between these time scales. As previously noted, to ensure exactly one nanosecond precision, hifitime stores durations as a tuple of integers, as these aren’t affected by successive rounding errors. The drawback of this approach is that we have to rewrite the arithmetics of durations on this (centuries, nanosecond) encoding and guarantee it satisfies expected properties.

This is where Kani comes in very handy. From its definition, Durations have a minimum and maximum value. On an unsigned 64-bit integer, we can store enough nanoseconds for four full centuries and a bit (but less than five centuries worth of nanoseconds). We want to normalize all operations such that the nanosecond counter stays within one century, unless we’ve reached the maximum (or minimum) number of centuries in which case, we want those nanoseconds to continue counting until the u64 bound is reached. Centuries are stored in a signed 16-bit integer, and are the only field that stores whether the duration is positive or negative.

At first sight, it seems like a relatively simple task to make sure that this math is correct. It turns out that handling edge cases near the min and max durations, or when performing operations between very large and very small durations requires special attention, or even when crossing the boundary of the reference epoch. For example, the TAI reference epoch is 01 January 1900, so when subtracting one nanosecond from 01 January 1900 at midnight, the internal duration representation goes from centuries: 0, nanoseconds: 0 to centuries: -1, nanoseconds: 3_155_759_999_999_999_999, as there are 3155759999999999999 + 1 = 3155760000000000000 nanoseconds in one century.

With Kani, we can check for all permutations of a definition of a Duration, and ensure that the decomposition of a Duration into its parts of days, hours, minutes, seconds, milliseconds, microseconds, and nanoseconds, never causes any overflow, underflow, or other unexpected behaviors. In hifitime, this is done simply by implementing Arbitrary for Duration, and calling the decompose() function on any duration. This test is beautiful in its simplicity: small code footprint for mighty guarantees, such could be the motto of Kani!

#[cfg(kani)]

impl Arbitrary for Duration {

#[inline(always)]

fn any() -> Self {

let centuries: i16 = kani::any();

let nanoseconds: u64 = kani::any();

Duration::from_parts(centuries, nanoseconds)

}

}

// (...)

#[cfg(kani)]

#[kani::proof]

fn formal_duration_normalize_any() {

let dur: Duration = kani::any();

// Check that decompose never fails

dur.decompose();

}

In the test above, if the call to decompose ever causes any overflow, underflow, division by zero, etc. then Kani will report an error and the exact value and bits inputted that caused the problem. This feedback is great, because one can just plugin those values into another test and debug it precisely. One will note that this test does not actually check the output value. That’s for two reasons. First, testing values would require developing either a formal specification or an independent implementation of the decompose function against which to check. Both options require quite a bit of effort, and the decompose function is really only used for displaying a duration in a human-readable format. Second, the purpose of the Hifitime Kani tests is to ensure that the aren’t any unsound operations. Finally, Hifitime has plenty of values that are explicitly tested for in the rest the tests.

Example of bug found with Kani

In a previous version of Hifitime, the normalize function would add two 64-bit unsigned integers to determine whether the duration being normalized would saturate to the MIN or MAX. Hifitime ensures that huge or tiny durations are saturated and don’t overflow. The exact erroneous code was as follows, and initially looks like it should be correct since we compute the remainder of the division by the number of nanoseconds in a century before adding it to the number of nanoseconds:

let rem_nanos = self.nanoseconds.rem_euclid(NANOSECONDS_PER_CENTURY);

if self.centuries == i16::MIN {

if rem_nanos + self.nanoseconds > Self::MIN.nanoseconds {

// We're at the min number of centuries already, and we have extra nanos, so we're saturated the duration limit

*self = Self::MIN;

}

// Else, we're near the MIN but we're within the MIN in nanoseconds, so let's not do anything here.

} // ...

With that code, Kani found a counter example via the formal_normalize_any test that triggered an overflow when the number of centuries was set to its absolute minimum and the number of nanoseconds was zero. In fact, if the number of centuries is minimized, Duration allows incrementing the number of nanoseconds until the maximum 64-bit unsigned integer (this allows Duration to cover a large time span). The report clearly displayed the input values that caused the overflow, and the exact line where the overflow(s) occurred.

- File src/duration.rs

- Function duration::Duration::normalize

- Line 285: [trace] attempt to add with overflow

- Line 291: [trace] attempt to add with overflow

- Function duration::Duration::normalize

(...)

Step 8962: Function MISSING, File MISSING, Line 0

extra_centuries = 5ul (00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000101)

Step 8963: Function MISSING, File MISSING, Line 0

-> core::num::<impl u64>::rem_euclid

Step 8964: Function MISSING, File MISSING, Line 0

self = 17480859535802999432ul (11110010 10011000 01111101 00100001 01011000 00001001 10100010 10001000)

Step 8965: Function MISSING, File MISSING, Line 0

rhs = 3155760000000000000ul (00101011 11001011 10000011 00000000 00000100 01100011 00000000 00000000)

Step 8966: Function MISSING, File MISSING, Line 0

<- core::num::<impl u64>::rem_euclid

Step 8967: Function MISSING, File MISSING, Line 0

rem_nanos = 1702059535802999432ul (00010111 10011110 11101110 00100001 01000010 00011010 10100010 10001000)

Step 8968: Function duration::Duration::normalize, File src/duration.rs, Line 285

if rem_nanos + self.nanoseconds > Self::MIN.nanoseconds { // We're at the min number of centuries already, and we have extra nanos, so we're saturated the duration limit *self = Self::MIN;

failure: duration::Duration::normalize.assertion.1: attempt to add with overflow

Now, the normalize function is not only simpler but also correct.

Conclusion

Kani has helped fix at least eight different categories of bugs in a single pull request: https://github.com/nyx-space/hifitime/pull/192. Most of these were bugs near the boundaries of a Duration definition: around the zero, maximum, and minimum durations. But many of the bugs were on important and common operations: partial equality, negation, addition, and subtraction operations. These bugs weren’t due to lax testing: there are over 74 integration tests with plenty of checks within each.

One of the great features of Kani is that it performs what is known as symbolic execution of programs, where inputs are modelled as symbolic variables covering whole ranges of values at once. All program behaviors possible under these inputs are analyzed for defects like arithmetic overflows or underflows, signed conversion overflow or underflow, etc. If a defect is possible for some values of the inputs, Kani will generate a counter example trace with concrete values triggering the defect.

Thanks to how Kani analyzes a program, tests can either have explicit post-conditions or not. A test with explicit post-conditions includes an assertion: execute a set of instructions and then check something. This is a typical test case.

Kani can also test code where there is no explicit condition to check. Instead, only the successive operations of a function call are executed, and each are tested by Kani for failure cases by analyzing the inputs and finding cases where inputs will lead to runtime errors like overflows. This approach is how most of the bugs in hifitime have been found.

Tests without explicit post-conditions effectively ensure that sanity of the operations in a given function call. Explicit tests provide the same while also checking for conditions after the calls. If either of these tests fail, Kani can provide a test failure report outlining the sequence of operations, and the binary representation of each intermediate operation, to help the developer gain an understanding of why their implementation is incorrect.

The overhead to implement tests in Kani is very low, and the benefits are immense. Hifitime has only eleven Kani tests, but that covers all of the core functionality. Basically, write a Kani verification like a unit test, add some assumptions on the values if desired, run the model verifier, and you’ve formally verified this part of the code (given the assumptions). Amazing!

Author bio

Chris Rabotin is a senior guidance, navigation, and controls (GNC) engineer at Rocket Lab USA. His day to day revolves around trajectory design and orbit determination of Moon-bounder missions, and developing GNC algorithms in C++ that run on spacecraft and lunar landers. On his free time, he architects and develops high fidelity astrodynamics software in Rust and Python (Nyx Space) and focuses way too much on testing and validation of its results. Chris has over twenty years of experience in Python and picked up Rust in 2017 after encountering yet another memory overrun in a vector math library in C.